Firefly’s Alpha Rocket Crashes Into Pacific Ocean After Failing to Reach Orbit

The failure resulted in the loss of a Lockheed Martin technology demonstration satellite.

Firefly Aerospace launched its two-stage Alpha rocket from California early Tuesday, but something went wrong about two-and-a-half minutes into the flight, rendering the rocket unable to deploy an experimental satellite into orbit for Lockheed Martin.

The Alpha rocket took off from Vandenberg Space Force Base about 140 miles northwest of Los Angeles at 6:37 am PDT (9:37 am EDT; 13:37 UTC), one day after Firefly called off a launch attempt due to a technical problem with ground support equipment.

Everything appeared to go well with the rocket's first-stage booster, powered by four kerosene-fueled Reaver engines, as the launcher ascended through fog and arced on a southerly trajectory over the Pacific Ocean. The booster stage jettisoned from Alpha's upper stage two-and-a-half minutes after liftoff, and that's when things went awry.

© Jack Beyer/Firefly Aerospace

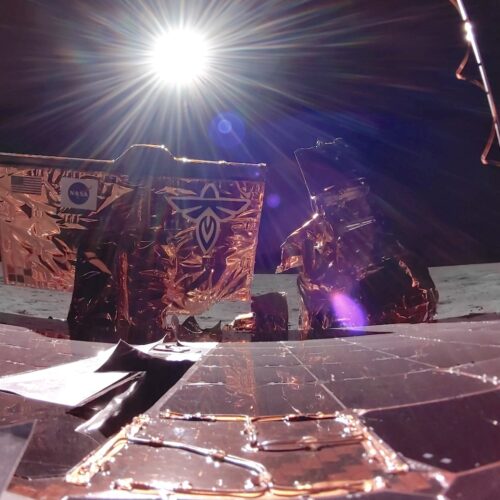

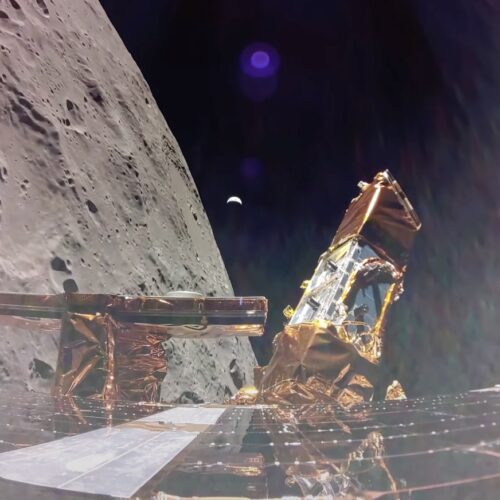

Firefly Aerospace's Blue Ghost science station accomplished a lot on the Moon in the last two weeks. Among other things, its instruments drilled into the Moon's surface, tested an extraterrestrial vacuum cleaner, and showed that future missions could use GPS navigation signals to navigate on the lunar surface.

These are all important achievements, gathering data that could shed light on the Moon's formation and evolution, demonstrating new ways of collecting samples on other planets, and revealing the remarkable reach of the US military's GPS satellite network.

But the pièce de résistance for Firefly's first Moon mission might be the daily dose of imagery that streamed down from the Blue Ghost spacecraft. A suite of cameras recorded the cloud of dust created as the lander's engine plume blew away the uppermost layer of lunar soil as it touched down March 2 in Mare Crisium, or the Sea of Crises. This location is in a flat basin situated on the upper right quadrant of the side of the Moon always facing the Earth.

© Firefly Aerospace

Welcome to Edition 7.35 of the Rocket Report! SpaceX's steamroller is still rolling, but for the first time in many years, it doesn't seem like it's rolling downhill. After a three-year run of perfect performance—with no launch failures or any other serious malfunctions—SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket has suffered a handful of issues in recent months. Meanwhile, SpaceX's next-generation Starship rocket is having problems, too. Kiko Dontchev, SpaceX's vice president of launch, addressed some (but not all) of these concerns in a post on X this week. Despite the issues with the Falcon 9, SpaceX has maintained a remarkable launch cadence. As of Thursday, SpaceX has launched 28 Falcon 9 flights since January 1, ahead of last year's pace.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don't want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Alpha rocket preps for weekend launch. While Firefly Aerospace is making headlines for landing on the Moon, its Alpha rocket is set to launch again as soon as Saturday morning from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California. The two-stage, kerosene-fueled rocket will launch a self-funded technology demonstration satellite for Lockheed Martin. It's the first of up to 25 launches Lockheed Martin has booked with Firefly over the next five years. This launch will be the sixth flight of an Alpha rocket, which has become a leader in the US commercial launch industry for dedicated missions with 1 ton-class satellites.

© SpaceX

Firefly Aerospace became the first commercial company to make a picture-perfect landing on the Moon early Sunday, touching down on an ancient basaltic plain, named Mare Crisium, to fulfill a $101 million contract with NASA.

The lunar lander, called Blue Ghost, settled onto the Moon's surface at 2:34 am CST (3:34 am EST; 08:34 UTC). A few dozen engineers in Firefly's mission control room monitored real-time data streaming down from a quarter-million miles away.

"Y’all stuck the landing, we’re on the Moon!" announced Will Coogan, the lander's chief engineer, to the Firefly team gathered in Leander, Texas, a suburb north of Austin. Down the street, at a middle-of-the-night event for Firefly employees, their families, and VIPs, the crowd erupted in applause and toasted champagne.

© Firefly Aerospace

CEDAR PARK, Texas—Early Sunday morning, while most of America is sleeping, a couple dozen engineers in Central Texas will have their eyes glued to monitors watching data stream in from a quarter-million miles away.

These ground controllers at Firefly Aerospace hope that their robotic spacecraft, named Blue Ghost, will become the second commercial mission to complete a soft landing on the Moon, following the landing of a spacecraft by Intuitive Machines last year. This is the first lunar mission for Firefly Aerospace, a company established in 2014 to develop a small satellite launcher.

Since then, Firefly has undergone changes in ownership, a bankruptcy, and a renaming. Recognizing that the company had to diversify to survive, Firefly executives began pursuing other business opportunities—spacecraft manufacturing, lunar missions, and a medium-class rocket—to go alongside its small Alpha launch vehicle.

© Firefly Aerospace

Welcome to Edition 7.32 of the Rocket Report! It's true that the US space program has always been political. Domestic and global politics have driven nearly all of the US government's decisions on major space issues, most notably President John F. Kennedy's challenge to land astronauts on the Moon amid intense Cold War competition with the Soviet Union. The Nixon administration's decision to end the Apollo program and focus on building a reusable Space Shuttle was a political move. More than 30 years later, the Clinton administration ordered a reevaluation NASA's plans for a massive space station in low-Earth orbit. In the post-Cold War zeitgeist of the 1990s, this resulted in Russia's inclusion in the International Space Station program. Flawed or not, these decisions were backstopped with some level of reasoning, debate, and national consensus-building. Today, the politics of space seem personal, small, and mean-spirited. Thankfully, there's a lot of launch action next week that might thrust us out of the abyss, even just for a moment.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don't want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Rocket Lab launches for the 60th time. It's safe to say Rocket Lab is an established player in the launch business. The company launched its 60th Electron rocket Tuesday from New Zealand, Space News reports. It was the second Electron launch of the year, coming just 10 days after Rocket Lab's previous mission. The payload was a new-generation small electro-optical reconnaissance satellite for BlackSky. Rocket Lab has not disclosed a projected number of Electron launches for the year beyond estimating it will be more than the 16 Electron missions in 2024. The company said on its launch webcast that the next Electron launch was planned from New Zealand in "a few short weeks."

© SpaceX

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lifted off from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida early Wednesday and deployed two commercial lunar landers on separate trajectories to reach the Moon in the next few months.

The mission began with a middle-of-the-night launch from Kennedy at 1:11 am EST (06:11 UTC) Wednesday. It took about an hour and a half for the Falcon 9 rocket to release both payloads into two slightly different orbits, ranging up to 200,000 and 225,000 miles (322,000 and 362,000 kilometers) from Earth.

The two robotic lunar landers—one from Firefly Aerospace based near Austin, Texas, and another from the Japanese space company ispace—will use their own small engines for the final maneuvers required to enter orbit around the Moon in the coming months.

© SpaceX