Psychedelics Allowed Ancient Peruvians to Consolidate Power, Study Says

Psychedelic drugs might have fundamentally changed pre-Incan society.

MarclSchauer/Shutterstock

The US is less than 250 years old, but some of its most important archaeological sites are older than the Viking seafarers, the Roman Empire, and the pyramids.

Many help tell the story of how the first humans came to North America. It's still a mystery exactly how and when people arrived, though it's widely believed they crossed the Bering Strait at least 15,000 years ago.

"As we get further back in time, as we get populations that are smaller and smaller, finding these places and interpreting them becomes increasingly difficult," archaeologist Kenneth Feder told Business Insider. He's the author of "Ancient America: Fifty Archaeological Sites to See for Yourself."

Some sites, like White Sands and Cooper's Ferry, have skeptics about the accuracy of their age. Still, they contribute to our understanding of some of the earliest Americans.

Others are more recent and highlight the different cultures that were spreading around the country, with complex buildings and illuminating pictographs.

Many of these places are open to the public, so you can see the US' ancient history for yourself.

National Park Service

Prehistoric camels, mammoths, and giant sloths once roamed what's now New Mexico, when it was greener and damper.

As the climate warmed around 11,000 years ago, the water of Lake Otero receded, revealing footprints of humans who lived among these extinct animals. Some even seemed to be following a sloth, offering a rare glimpse into ancient hunters' behavior.

Recent research puts some of these fossilized footprints at between 21,000 and 23,000 years old. If the dates are accurate, the prints would predate other archaeological sites in the US, raising intriguing questions about who these people were and how they arrived in the Southwestern state.

"Where are they coming from?" Feder said. "They're not parachute dropping in New Mexico. They must have come from somewhere else, which means there are even older sites." Archaeologists simply haven't found them yet.

While visitors can soak in the sight of the eponymous white sands, the footprints are currently off-limits.

AP Photo/Keith Srakocic

In the 1970s, archaeologist James M. Adovasio sparked a controversy when he and his colleagues suggested stone tools and other artifacts found in southwestern Pennsylvania belonged to humans who had lived in the area 16,000 years ago.

For decades, scientists had been finding evidence of human habitation that all seemed to be around 12,000 to 13,000 years old, belonging to the Clovis culture. They were long believed to have been the first to cross the Bering land bridge. Humans who arrived in North America before this group are often referred to as pre-Clovis.

At the time, skeptics said that the radiocarbon dating evidence was flawed, AP News reported in 2016. In the years since, more sites that appear older than 13,000 years have been found across the US.

Feder said Adovasio meticulously excavated the site, but there's still no clear consensus about the age of the oldest artifacts. Still, he said, "that site is absolutely a major, important, significant site." It helped archaeologists realize humans started arriving on the continent before the Clovis people.

The dig itself is on display at the Heinz History Center, allowing visitors to see an excavation in person.

Loren Davis/Oregon State University

One site that's added intriguing evidence to the pre-Clovis theory is located in western Idaho. Humans living there left stone tools and charred bones in a hearth between 14,000 and 16,000 years ago, according to radiocarbon dating. Other researchers put the dates closer to 11,500 years ago.

These stemmed tools are different from the Clovis fluted projectiles, researchers wrote in a 2019 Science Advances paper.

Some scientists think humans may have been traveling along the West Coast at this time, when huge ice sheets covered Alaska and Canada. "People using boats, using canoes could hop along that coast and end up in North America long before those glacial ice bodies decoupled," Feder said.

Cooper's Ferry is located on traditional Nez Perce land, which the Bureau of Land Management holds in public ownership.

Texas A&M University via Getty Images

In the early 1980s, former Navy SEAL Buddy Page alerted paleontologists and archaeologists to a sinkhole nicknamed "Booger Hole" in the Aucilla River. There, the researchers found mammoth and mastodon bones and stone tools.

They also discovered a mastodon tusk with what appeared to be cut marks believed to be made by a tool. Other scientists have returned to the site more recently, bringing up more bones and tools. They used radiocarbon dating, which established the site as pre-Clovis.

"The stone tools and faunal remains at the site show that at 14,550 years ago, people knew how to find game, fresh water and material for making tools," Michael Waters, one of the researchers, said in a statement in 2016. "These people were well-adapted to this environment."

Since the site is both underwater and on private property, it's not open to visitors.

AP Photo/Jeff Barnard

Scientists study coprolites, or fossilized poop, to learn about the diets of long-dead animals. Mineralized waste can also reveal much more. In 2020, archaeologist Dennis Jenkins published a paper on coprolites from an Oregon cave that were over 14,000 years old.

Radiocarbon dating gave the trace fossils' age, and genetic tests suggested they belonged to humans. Further analysis of coprolites added additional evidence that a group had been on the West Coast 1,000 years before the Clovis people arrived.

Located in southcentral Oregon, the caves appear to be a piece of the puzzle indicating how humans spread throughout the continent thousands of years ago.

The federal Bureau of Land Management owns the land where the caves are found, and they are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Charles Holmes/University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Whenever people arrived in the Americas, they crossed from Siberia into Beringia, an area of land and sea between Russia and Canada and Alaska. Now it's covered in water, but there was once a land bridge connecting them.

The site in Alaska with the oldest evidence of human habitation is Swan Point, in the state's eastern-central region. In addition to tools and hearths dating back 14,000 years, mammoth bones have been found there.

Researchers think this area was a kind of seasonal hunting camp. As mammoths returned during certain times of the years, humans would track them and kill them, providing plentiful food for the hunter-gatherers.

While Alaska may have a wealth of archaeological evidence of early Americans, it's also a difficult place to excavate. "Your digging season is very narrow, and it's expensive," Feder said. Some require a helicopter to reach, for example.

Dick Kent/FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images

In 1929, 19-year-old James Ridgley Whiteman found mammoth bones along with fluted projectile points near Clovis, New Mexico. The Clovis people who made these tools were named for this site.

Researchers studying the site began to realize the artifacts found at the site belonged to different cultures. Clovis points are typically larger than Folsom flutes, which were first found at another archaeological site in New Mexico.

For decades after Whiteman's discovery, experts thought the Clovis people were the first to cross the Bering land bridge from Asia around 13,000 years ago. Estimates for humans' arrival is now thought to be at least 15,000 years ago.

Eastern New Mexico University's Blackwater Draw Museum grants access to the archaeological site between April and October.

Ben Potter/University of Alaska, Fairbanks

One reason the dates of human occupation in North America is so contentious is that very few ancient remains have been found. Among the oldest is a child from Upward Sun River, or Xaasaa Na', in Central Alaska.

Archaeologists found the bones of the child in 2013. Local indigenous groups refer to her as Xach'itee'aanenh t'eede gay, or Sunrise Girl-Child. Genetic testing revealed the 11,300-year-old infant belonged to a previously unknown Native American population, the Ancient Beringians.

Based on the child's genetic information, researchers learned that she was related to modern Native Americans but not directly. Their common ancestors started becoming genetically isolated 25,000 years ago before dividing into two groups after a few thousand years: the Ancient Berignians and the ancestors of modern Native Americans.

According to this research, it's possible humans reached Alaska roughly 20,000 years ago.

National Park Service

Stretching over 80 feet long and 5 feet tall, the rows of curved mounds of Poverty Point are a marvel when viewed from above. Over 3,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers constructed them out of tons of soil. Scientists aren't sure exactly why people built them, whether they were ceremonial or a display of status.

The artifacts various groups left behind indicate the site was used off and on for hundreds of years and was a meeting point for trading. People brought tools and rocks from as far as 800 miles away. Remains of deer, fish, frogs, alligators, nuts, grapes, and other food have given archaeologists insights into their diets and daily lives.

You can see the World Heritage Site for yourself year-round.

Neal Herbert/National Park Service

Though remote, the multicolored walls of Horseshoe Canyon have long attracted visitors. Some of its artifacts date back to between 9,000 and 7,000 BCE, but its pictographs are more recent. Some tests date certain sections to around 2,000 to 900 years ago.

The four galleries contain life-sized images of anthropomorphic figures and animals in what's known as the Barrier Canyon style. Much of this art is found in Utah, produced by the Desert Archaic culture.

The pictographs may have spiritual and practical significance but also help capture a time when groups were meeting and mixing, according to the Natural History Museum of Utah.

It's a difficult trek to get to the pictographs (and the NPS warns it can be dangerously hot in summer) but are amazing to view in person, Feder said. "These are creative geniuses," he said of the artists.

Michael Denson/National Park Service

Situated in the Navajo Nation, Canyon de Chelly has gorgeous desert views and thousands of years of human history. Centuries ago, Ancestral Pueblo and Hopi groups planted crops, created pictographs, and built cliff dwellings.

Over 900 years ago, Puebloan people constructed the White House, named for the hue of its clay. Its upper floors sit on a sandstone cliff, with a sheer drop outside the windows.

Navajo people, also known as Diné, still live in Canyon de Chelly. Diné journalist Alastair Lee Bitsóí recently wrote about visiting some of the sacred and taboo areas. They include Tsé Yaa Kin, where archaeologists found human remains.

In the 1860s, the US government forced 8,000 Navajo to relocate to Fort Sumner in New Mexico. The deadly journey is known as the "Long Walk." Eventually, they were able to return, though their homes and crops were destroyed.

A hike to the White House is the only one open to the public without a Navajo guide or NPS ranger.

Shutterstock/Don Mammoser

In the early 1900s, two women formed the Colorado Cliff Dwelling Association, hoping to preserve the ruins in the state's southwestern region. A few years later, President Theodore Roosevelt signed a bill designating Mesa Verde as the first national park meant to "preserve the works of man."

Mesa Verde National Park holds hundreds of dwellings, including the sprawling Cliff Palace. It has over 100 rooms and nearly two dozen kivas, or ceremonial spaces.

Using dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, archaeologists learned when Ancestral Pueblo people built some of these structures and that they migrated out of the area by the 1300s.

Feder said it's his favorite archaeological site he's visited. "You don't want to leave because you can't believe it's real," he said.

Tourists can view many of these dwellings from the road, but some are also accessible after a bit of a hike. Some require extra tickets and can get crowded, Feder said.

Matt Gush/Shutterstock

Cahokia has been called one of North America's first cities. Not far from present-day St. Louis, an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people lived in dense settlements roughly 1,000 years ago. Important buildings sat atop large mounds, which the Mississippians built by hand, The Guardian reported.

At the time, it was thriving with hunters, farmers, and artisans. "It's an agricultural civilization," Feder said. "It's a place where raw materials from a thousand miles away are coming in." Researchers have also found mass graves, potentially from human sacrifices.

The inhabitants built circles of posts, which one archaeologist later referred to as "woodhenges," as a kind of calendar. At the solstices, the sun would rise or set aligned with different mounds.

After a few hundred years, Cahokia's population declined and disappeared by 1350. Its largest mound remains, and some aspects have been reconstructed.

While Cahokia is typically open to the public, parts are currently closed for renovations.

MyLoupe/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Perched on a limestone cliff in Camp Verde, Arizona, this site is an apartment, not a castle, and is unrelated to the Aztec ruler Montezuma.

The Sinagua people engineered the five-story, 20-room building around 1100. It curves to follow the natural line of the cliff, which would have been more difficult than simply making a straight building, Feder said.

"These people were architects," he said. "They had a sense of beauty."

The inhabitants were also practical, figuring out irrigation systems and construction techniques, like thick walls and shady spots, to help them survive the hot, dry climate.

Feder said the dwelling is fairly accessible, with a short walk along a trail to view it, though visitors can't go inside the building itself.

Human presence in high-altitude open areas during the Ice Age is not just a possibility, but a reality, Marta Sánchez de la Torre writes

© AP Photo/Aritz Parra, File

Findings predate founding of Football Association by centuries and could explain Scotland’s early dominance of international football

© Getty

In 2022, we told you about a study reporting evidence that an ancient Peruvian people called the Wari laced the beer served at their feasts with hallucinogens—particularly a substance derived from the seeds of the vilca tree, which was common in the region during the Middle Horizon period (circa 850 CE) when the Wari empire thrived. This may have helped the Wari forge political alliances and expand their empire.

Now archaeologists have discovered direct evidence that the use of vilca was a common practice some 1,000 years earlier than the Wari, thanks to analysis of artifacts unearthed at Chavín de Huántar, located about 250 kilometers north of Lima, Peru. And the Chavín people may have used it for a different purpose: to reinforce social hierarchies by limiting consumption of those substances to an elite few, according to a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

There is ample evidence that humans in many cultures throughout history used various hallucinogenic substances in religious ceremonies or shamanic rituals. That includes ancient Egypt, as well as ancient Greek, Vedic, Maya, Inca, and Aztec cultures. The Urarina people who live in the Peruvian Amazon Basin still use a psychoactive brew called ayahuasca in their rituals, and Westerners seeking their own brand of enlightenment have been known to participate. The Wari empire lasted from around 500 CE to 1100 CE in the central highlands of Peru.

© Daniel Contreras

Archaeologists recently unearthed a bone projectile point someone dropped on a cave floor between 70,000 and 80,000 years ago—which, based on its location, means that said someone must have been a Neanderthal.

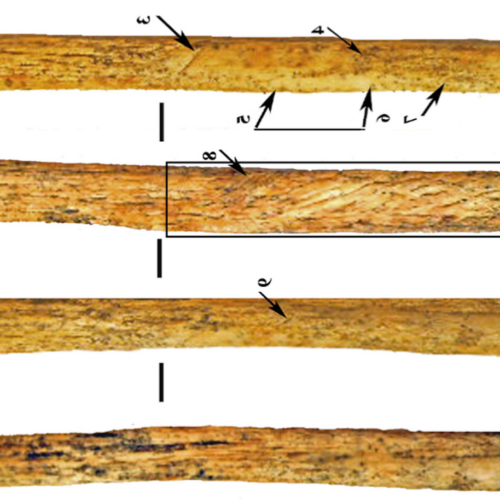

The point (or in paleoarchaeologist Liubov V. Golovanova and colleagues’ super-technical archaeological terms, “a unique pointy bone artifact”) is the oldest bone tip from a hunting weapon ever found in Europe. It’s also evidence that Neanderthals figured out how to shape bone into smooth, aerodynamic projectiles on their own, without needing to copy those upstart Homo sapiens. Along with the bone tools, jewelry, and even rope that archaeologists have found at other Neanderthal sites, the projectile is one more clue pointing to the fact that Neanderthals were actually pretty sharp.

Archaeologists found the bone point in Mezmaiskaya Cave, high in the Caucasus Mountains (Mezmaiskaya is also home to the remains of three Neanderthals who lived around 90,000 years ago; anthropologists sequenced samples of their DNA in earlier studies). Herbivore teeth from the same layer of sediment dated to around 70,000 years old, and the bone point’s position near the bottom of that layer probably makes it closer to 80,000 or 70,000 years old. That makes it the oldest bone projectile point ever found in Europe (so far).

© Golovanova et al. 2025

It's a regrettable reality that there is never time to cover all the interesting scientific stories we come across each month. In the past, we've featured year-end roundups of cool science stories we (almost) missed. This year, we're experimenting with a monthly collection. April's list includes new research on tattooed tardigrades, the first live image of a colossal baby squid, the digital unfolding of a recently discovered Merlin manuscript, and an ancient Roman gladiator whose skeleton shows signs of being gnawed by a lion.

Popular depictions of Roman gladiators in combat invariably include battling not just human adversaries but wild animals. We know from surviving texts, imagery, and artifacts that such battles likely took place. But hard physical evidence is much more limited. Archaeologists have now found the first direct osteological evidence: the skeleton of a Roman gladiator who encountered a wild animal in the arena, most likely a lion, based on bite marks evident on the pelvic bone, according to a paper published in the journal PLoS ONE.

The skeleton in question was that of a young man, age 26 to 35, buried between 200–300 CE near what is now York, England, formerly the Roman city of Eboracum. It's one of several such skeletons, mostly young men whose remains showed signs of trauma—hence the suggestion that it could be a gladiator burial site. "We used a method called structured light scanning [to study the skeleton]," co-author Tim Thompson of Maynooth University told Ars. "It's a method of creating a 3D model using grids of light. It's not like X-ray or CT, in that it only records the surface (not internal) features, but since it uses light and not X-rays etc, it is much safer, cheaper, and more portable. We have published a fair bit on this and shown its use in both archaeological and forensic contexts."

© Schmidt Ocean Institute

The buried roots and stumps of an ancient forest in southern China are the charred remains of an ancient war and the burning of a capital city, according to a recent study from researchers who carbon-dated the stumps and measured charcoal and pollen in the layers of peat surrounding them.

It may not be obvious today, but there’s an ancient forest hidden beneath the farmland of southern China’s Pearl River Delta. Spread across 2,000 square kilometers are thick layers of waterlogged peat, now covered by agriculture. It’s all that is left of what used to be a thriving wetland ecosystem, home to forests of Chinese swamp cypress along with elephants, tigers, crocodiles, and tropical birds. But the peat hides the buried, preserved stumps and roots of cypress trees; some of the largest stumps are almost 2 meters wide, and many have burn marks on their tops.

“These peat layers are locally known as ‘buried ancient forest,’ because many buried trees appear fresh and most stumps are found still standing,” writes Ning Wang of the Chinese Academy of Scientists, who along with colleagues, authored the recent paper. It turns out that the eerie buried forest is the last echo of the Han army’s invasion during a war about 2,100 years ago.

© Daderot

The first evidence that hominins butchered several animals at the site in Romania at least 1.95 million years ago has been revealed

© Ohio University

The colonial victory against the British in the American Revolutionary War was far from a predetermined outcome. In addition to good strategy and the timely appearance of key allies like the French, Continental soldiers relied on several key technological innovations in weaponry. But just how accurate is an 18th-century musket when it comes to hitting a target? Did the rifle really determine the outcome of the war? And just how much damage did cannon inflict? A team of military weapons experts and re-enactors set about testing some of those questions in a new NOVA documentary, Revolutionary War Weapons.

The documentary examines the firing range and accuracy of Brown Bess muskets and long rifles used by both the British and the Continental Army during the Battles of Lexington and Concord; the effectiveness of Native American tomahawks for close combat (no, they were usually not thrown as depicted in so many popular films, but there are modern throwing competitions today); and the effectiveness of cannons against the gabions and other defenses employed to protect the British fortress during the pivotal Siege of Yorktown. There is even a fascinating segment on the first military submarine, dubbed "the Turtle," created by American inventor David Bushnell.

To capture all the high-speed ballistics action, director Stuart Powell relied upon a range of high-speed cameras called the Phantom Range. "It is like a supercomputer," Powell told Ars. "It is a camera, but it doesn't feel like a camera. You need to be really well-coordinated on the day when you're using it because it bursts for, like, 10 seconds. It doesn't record constantly because it's taking so much data. Depending on what the frame rate is, you only get a certain amount of time. So you're trying to coordinate that with someone trying to fire a 250-year-old piece of technology. If the gun doesn't go off, if something goes wrong on set, you'll miss it. Then it takes five minutes to reboot and get ready for the new shot. So a lot of the shoot revolves around the camera; that's not normally the case."

© GBH/NOVA

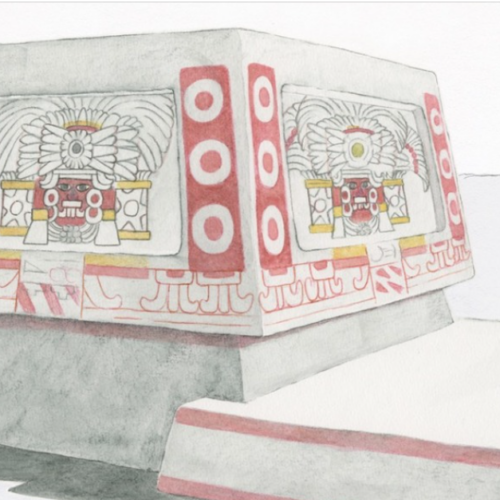

A family altar in the Maya city of Tikal offers a glimpse into events in an enclave of the city’s foreign overlords in the wake of a local coup.

Archaeologists recently unearthed the altar in a quarter of the Maya city of Tikal that had lain buried under dirt and rubble for about the last 1,500 years. The altar—and the wealthy household behind the courtyard it once adorned—stands just a few blocks from the center of Tikal, one of the most powerful cities of Maya civilization. But the altar and the courtyard around it aren’t even remotely Maya-looking; their architecture and decoration look like they belong 1,000 kilometers to the west in the city of Teotihuacan, in central Mexico.

The altar reveals the presence of powerful rulers from Teotihuacan who were there at a time when a coup ousted Tikal’s Maya rulers and replaced them with a Teotihuacan puppet government. It also reveals how hard those foreign rulers fell from favor when Teotihuacan’s power finally waned centuries later.

© Heather Hurst

The remains of three children were found at the altar in Tikal National Park in Guatemala

© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

New discoveries are overturning the assumptions that used to be made about a woman’s place in society, writes Emily Hauser

© Archaeological Park of Pompeii/Alfio Giannotti