Decentralized Instagram-Killer Pixelfed Gets a Mobile App

The Fediverse website offers users the same photo-sharing experience as Instagram without any of the surveillance.

Anticipating that 2025 will be an "intense year" requiring rapid innovation, Mark Zuckerberg reportedly announced that Meta would be cutting 5 percent of its workforce—targeting "lowest performers."

Bloomberg reviewed the internal memo explaining the cuts, which was posted to Meta's internal Workplace forum Tuesday. In it, Zuckerberg confirmed that Meta was shifting its strategy to "move out low performers faster" so that Meta can hire new talent to fill those vacancies this year.

"I’ve decided to raise the bar on performance management," Zuckerberg said. "We typically manage out people who aren’t meeting expectations over the course of a year, but now we’re going to do more extensive performance-based cuts during this cycle."

© Bloomberg / Contributor | Bloomberg

Chinese officials have reportedly discussed selling TikTok's US operations to Elon Musk as the threat of a US ban looms.

Sources "familiar with the matter" told Bloomberg that Chinese officials would "strongly prefer" that ByteDance remain in control of TikTok US, but if TikTok's bid to get the Supreme Court to block the ban fails, ByteDance wants to be prepared with "contingency plans."

One of those supposed contingency plans would apparently see Musk operating TikTok as part of X (formerly Twitter) operations. Under that scenario, Musk's X would control TikTok US, sources said, and thus gain access to a massive trove of TikTok data that the US has alleged poses a grave national security risk if left under a Chinese-owned company's control.

© The Washington Post / Contributor | The Washington Post

Facebook; Getty Images; Chelsea Jia Feng/BI

Mark Zuckerberg said he thinks Meta needs more "masculine energy" and that the company's culture has been "neutered" in the last few years.

There might be a disconnect between Zuckerberg's ambitions — which he shared on Joe Rogan's podcast last week — and the actual social platforms he runs. In the US, more women use Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp than men. (Global numbers aren't available.)

Facebook — still the most popular social network — is where the gender divide gets even more obvious. A 2024 Pew Research Center report on social media use showed that 61% of adult men in the US used Facebook "at all," while 78% of adult women did. That 17-point difference is greater than the divide between men's and women's use of any other social network except Pinterest.

If you look back at a similar 2013 Pew report, 66% of men and 72% of women used Facebook. However, the most current metric is slightly different, measuring internet-using adults, not all adults. But even a decade ago, there was still a noticeable gap between the genders — and it's gotten bigger.

Quite simply, Facebook is in some way a women's platform — or at least it leans that way.

Now, of course, it's an exaggeration to say that men "don't" use Facebook — a majority of them say they use it or have an account.

But that doesn't tell us how they're using it, exactly — if they're frequently posting or engaging or just checking in once a month. I don't have data about which gender actually uses Facebook more, but I have some ideas based on both research and my own anecdotal experience that suggest that women are driving the daily conversations on the platform.

It's important to note that these stats are for US users, which makes up only a fraction of the 3 billion-plus users. Globally, the gender breakdown may be quite different; Meta doesn't release its own statistics on gender and declined to comment for this story.

Why do more women than men use Facebook? I have some theories, some of which are sweeping generalizations about gender — like that some men don't find as much value or pleasure in keeping up with old acquaintances as women do.

You can see in the Pew study that other platforms like X (Twitter) and Reddit have more male users. This doesn't seem surprising at all, and you can probably come up with some easy theories in your mind right now as to why.

For our purposes, we're talking about traditional gender roles here. (I recognize the irony in talking about gender this way when Meta has just changed its content rules to allow for more hateful rhetoric about trans people). I am sure that there are many people out there — perhaps even you, dear reader — who don't use Facebook this way and can't relate to any of this. That's OK.

@zuck via Instagram

There is some interesting academic research that can help us try to make sense of this female energy. A study published last year looked into perceptions of masculinity and the use of social media. Participants were to rate the masculinity or femininity of a person who posts either frequently or infrequently. What they found was that consistently, people rated men who post frequently as being less masculine.

Andrew Edelblum, assistant professor of marketing at the University of Dayton, who authored the paper, and his coauthor tried different "bias-breakers" in their surveys: What if the man wasn't posting about himself but posting about other people? Or what if the man was posting not as a regular person but as a professional influencer who was doing it for work? They found that the perception remained the same — frequent posting was viewed as feminine.

Perhaps men, sensing this perception, stop themselves from being active on Facebook.

"What we found is, and we're drawing on, what at this point is kind of a well-known phenomenon of 'precarious manhood,'" Edelblum told Business Insider. "It's essentially the idea that 'man card' credentials are really hard to gain but very easy to lose."

Anecdotally, I have noticed that Facebook seems to be predominantly used by women. My male friends rarely use Facebook, and as I poke around many corners of the platform, either for professional or personal reasons, I tend to see fewer men posting in groups or even listing things on Marketplace.

I'm incredibly active on Facebook — I spend hours there a week, mainly in groups that are nearly all women — groups for parenting, fans of "Vanderpump Rules," shopping, or decorating (now that I think about it, perhaps Facebook being a matriarchal society is why I have more unregretted user seconds spent on there than, say, X).

I also see some well-worn gendered division of household labor dynamics play out: For example, my kid's school has an active Facebook Group, but it's almost all moms. Same with a group for hiring local babysitters. Even a non-gendered general local town group or a Buy Nothing group seems to be mainly used by women.

My husband deactivated his own Facebook account in 2009 after deciding it was "uncool," but I recently whined to him that it was unfair that I had to be the sole Facebook admin for the family. (He made a new account with a fake name so he can browse Marketplace at least.)

Mark Zuckerberg's comment about wanting more "masculine energy" was about his company's internal culture and the need to be more aggressive instead of accommodating external critics.

This has seemed to play out in some ways that appear boorish, like removing the tampons in the men's bathrooms that were meant to accommodate a handful of trans or nonbinary employees and visitors.

I do wonder if part of Zuckberg's apparent personal King of the Bros rebrand is hoping to entice younger men back to Facebook, trying to demonstrate that you can be both masculine and a frequent Facebook poster.

It seems that his comments and his actions aren't really meant for the nosy housewives who are among the biggest users of his platforms. His peacocking, new politics, and Joe Rogan appearances are meant for Silicon Valley workers who work at or invest in his products — and many of them seem to love it.

But somewhere, I do worry that people have forgotten something that seems clear to me: Facebook is powered by feminine energy.

AP; Francois Mori/AP

Meta's Mark Zuckerberg and Apple's Tim Cook have a long-standing feud.

The two tech titans have been bickering since at least 2014, trading barbs over each other's products and business models. Over the years, their battle has escalated to include public jabs, pointed ad campaigns, and even a legal dispute.

In January, Zuckerberg went on Joe Rogan's podcast and said Apple hasn't "really invented anything great in a while" since the iPhone launched under Steve Jobs.

Here's when the rivalry began, and what's happened since.

AP

In September 2014, Cook gave an in-depth interview with Charlie Rose that touched on a range of topics, including privacy.

During the interview — which took place in the weeks following the infamous leaks of multiple female celebrities' nude photos stored on their iCloud accounts — Cook espoused Apple's commitment to privacy while denouncing the business models of companies like Google and Facebook.

"I think everyone has to ask, how do companies make their money? Follow the money," Cook said. "And if they're making money mainly by collecting gobs of personal data, I think you have a right to be worried. And you should really understand what's happening to that data."

Shortly after, Cook reiterated his stance in an open letter on Apple's dedicated privacy site.

"A few years ago, users of Internet services began to realize that when an online service is free, you're not the customer. You're the product," Cook wrote.

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

In an interview with Time later that year, Zuckerberg was reportedly visibly irritated by Cook's assertions.

"A frustration I have is that a lot of people increasingly seem to equate an advertising business model with somehow being out of alignment with your customers," Zuckerberg told Time's Lev Grossman. "I think it's the most ridiculous concept. What, you think because you're paying Apple that you're somehow in alignment with them? If you were in alignment with them, then they'd make their products a lot cheaper!"

Edgar Su/Reuters

In 2018, a whistleblower revealed that consulting firm Cambridge Analytica harvested user data without consent from 50 million users.

During an interview with Kara Swisher and Chris Hayes in the months following, Cook was asked what he would do if he was in Zuckerberg's shoes.

Cook responded: "What would I do? I wouldn't be in this situation."

Cook said that Facebook should have regulated itself when it came to user data, but that "I think we're beyond that here." He also doubled down on his stance that Facebook considers its users its product.

"The truth is, we could make a ton of money if we monetized our customer — if our customer was our product," Cook said. "We've elected not to do that."

Andrew Harnik/AP

"You know, I find that argument, that if you're not paying that somehow we can't care about you, to be extremely glib. And not at all aligned with the truth," Zuckerberg said during an interview on The Ezra Klein Show podcast.

He refuted the idea that Facebook isn't focused on serving people and once again criticized the premium Apple places on its products.

"I think it's important that we don't all get Stockholm Syndrome and let the companies that work hard to charge you more convince you that they actually care more about you," he said. "Because that sounds ridiculous to me."

Yuri Gripas/Reuters

In November 2018, The New York Times published a blockbuster report detailing the fallout from the Cambridge Analytica scandal. The Times reported that Cook's comments had "infuriated" Zuckerberg, who ordered employees on his management team who used iPhones to switch to Android.

Soon after the report published, Facebook wrote a blog post refuting some of the reporting by The Times — but not the Zuckerberg-Cook feud.

"Tim Cook has consistently criticized our business model and Mark has been equally clear he disagrees. So there's been no need to employ anyone else to do this for us," Facebook wrote. "And we've long encouraged our employees and executives to use Android because it is the most popular operating system in the world."

MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images;Xinhua/Liu Jie via Getty Images;Insider

According to The Times, Zuckerberg asked Cook for his advice following the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Cook told Zuckerberg Facebook should delete the user data his company collects from outside of its family of apps, which "stunned" Zuckerberg and was akin to Cook saying Facebook's business was "untenable," The Times reported.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

During a company-wide meeting, Zuckerberg openly criticized Apple, saying it has a "unique stranglehold as a gatekeeper on what gets on phones," according to a report from BuzzFeed News.

Zuckerberg also said that the App Store blocks innovation and competition and "allows Apple to charge monopoly rents," BuzzFeed reported.

Apple has been facing antitrust scrutiny from Congress and has been strongly criticized by developers — most notably "Fortnite" creator Epic Games — for the 30% fee it takes from App Store purchases. In 2020, Facebook said Apple blocked an update to Facebook's iOS app that would have informed users about the fee Apple charges.

Apple

That version of Apple's smartphone operating system, iOS, made it so that iPhone app developers would need permission from users to collect and track their data. While this affects any company that makes iOS apps, it also has a direct impact on Facebook's advertising business: It uses data tracking to dictate which ads are served to users.

In an August 2020 blog post, Facebook said it may be forced to shut down Audience Network for iOS, a tool that personalizes ads in third-party apps.

"This is not a change we want to make, but unfortunately, Apple's updates to iOS 14 have forced this decision," Facebook said.

The complaints from Facebook and other developers led Apple to temporarily delay the new privacy tools, saying it wanted to "give developers the time they need to make the necessary changes."

—Dave Stangis (@DaveStangis) December 16, 2020

In the ads, Facebook argued that the changes would hurt small businesses that advertise on Facebook's platform.

"Without personalized ads, Facebook data shows that the average small business advertiser stands to see a cut of over 60% in their sales for every dollar they spend," the ad reads, which was posted by Twitter user Dave Stangis.

Apple hit back, telling Business Insider that it was "standing up for our users."

"Users should know when their data is being collected and shared across other apps and websites — and they should have the choice to allow that or not," an Apple spokesperson said.

Epic Games; Getty Images

Epic Games had accused Apple of violating antitrust laws and engaging in anticompetitive behavior regarding the App Store's fees and policies.

Facebook said it planned to help Epic with discovery for the trial.

When discussing Facebook's suite of messaging apps during the company's fourth-quarter earnings call, Zuckerberg made a clear dig at Apple, saying the iPhone maker made "misleading" privacy claims.

"Now Apple recently released so-called nutrition labels, which focused largely on metadata that apps collect rather than the privacy and security of people's actual messages, but iMessage stores non-end-to-end encrypted backups of your messages by default unless you disable iCloud," Zuckerberg said.

Zuckerberg went on to describe Apple as "one of our biggest competitors" and said that because Apple is increasingly relying on services to fuel its business, it "has every incentive to use their dominant platform position to interfere with how our apps and other apps work, which they regularly do to preference their own."

"This impacts the growth of millions of businesses around the world," he added.

AP

During a speech at the European Computers, Privacy and Data Protection Conference the same week, Cook discussed business models that prioritize user engagement and rely on user data to make money. Though he didn't mention Facebook by name, Cook made several references that alluded to the platform.

"At a moment of rampant disinformation and conspiracy theories juiced by algorithms, we can no longer turn a blind eye to a theory of technology that says all engagement is good engagement — the longer the better — and all with the goal of collecting as much data as possible," Cook said.

Nick Wass/Associated Press

The initiative, titled "Good Ideas Deserve to be Found," makes the case that personalized ads help Facebook users discover small businesses, particularly during the pandemic.

"Every business starts with an idea, and being able to share that idea through personalized ads is a game changer for small businesses," Facebook said in a blog post announcing the theme. "Limiting the use of personalized ads would take away a vital growth engine for businesses."

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

During a podcast interview with Kara Swisher, Cook said that he believes society is in a privacy crisis and that he's been "shocked" that there's been pushback to the new feature to this degree.

"We know these things are flimsy arguments," Cook told The Times. "I think that you can do digital advertising and make money from digital advertising without tracking people when they don't know they're being tracked."

Cook also said he doesn't view Facebook as a competitor, contrary to what Zuckerberg has said.

"Oh, I think that we compete in some things," Cook said. "But no, if I may ask who our biggest competitor are, they would not be listed. We're not in the social networking business."

Alex Wong/Getty Images

"The impact of iOS overall as a headwind on our business in 2022 is on the order of $10 billion," then-Meta CFO David Wehner estimated in an earnings call that year.

Getty Images

Apple, for its part, said in January 2024 that it had "fully complied" with the injunction.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Apple released its Vision Pro headset in February 2024, and Zuckerberg was quick to offer his critique of the competitor to Meta's Quest headsets.

"I have to say that before this, I expected that Quest would be the better value for most people since it's really good and like seven times less expensive, but after using [Vision Pro] I don't just think that Quest is the better value, it's the better product, period," Zuckerberg said in a video on Threads. "They have different strengths, but overall Quest is better for the vast majority of things that people use mixed reality for."

Zuckerberg says many people "assumed that Vision Pro would be higher quality because it's Apple and it costs $3,000 more."

"I know that some fanboys get upset whenever anyone dares to question if Apple's going to be the leader in a new category," he said. "But the reality is that every generation of computing has an open and a closed model. And yeah, in mobile, Apple's closed model won, but it's not always that way."

In Meta's first quarter earnings call in April, Zuckerberg said he didn't think AR glasses would find mainstream success without "full holographic displays."

"I still think that that's going to be awesome and is the long-term mature state for the product," he said. "But now, it seems pretty clear that there's also a meaningful market for fashionable AI glasses without a display."

Meta CTO Andrew Bosworth has also taken shots at Apple over its Vision Pro.

"As soon as I put the headset on, I can see what trade-offs they made and why they made them. And, perhaps definitionally, those aren't the trade-offs I would have made," he said.

Bosworth called the Vision Pro's motion blur "really distracting" and said the headset was "very uncomfortable to use."

Alex Wong via Getty Images

Apple months ago rejected the possibility of integrating Meta's Llama AI chatbot into the iPhone because it doesn't consider Meta's privacy practices up to par, Bloomberg's Mark Gurman reported in June 2024, citing people with knowledge of the matter.

Apple has since launched iOS 18, which includes a partnership with OpenAI to integrate ChatGPT into the iPhone's software.

Meta

In an episode of the "Joe Rogan Experience" podcast released in January 2025, he said Apple hasn't "really invented anything great in a while" since the iPhone.

"It's like Steve Jobs invented the iPhone and now they're just kind of sitting on it 20 years later," he said on the podcast.

Zuck added that Apple has been "squeezing people" for money with the 30% commission the company charges developers for selling paid apps through the App Store.

"They build stuff like Airpods, which are cool, but they've just thoroughly hamstrung the ability for anyone else to build something that can connect to the iPhone in the same way," he said.

Mastodon announced Monday that it's shifting its structure over the next six months to become wholly owned by a European nonprofit organization—"affirming the intent that Mastodon should not be owned or controlled by a single individual."

This takes control of the social network away from its previous "ultimate decision-maker," Eugen Rochko. As founder, Rochko initially took the reins to ensure the decentralized platform would never be for sale and "would be free of the control of a single wealthy individual." His grand vision remains to leave Mastodon users in control of the social network, making their own decisions about what content is allowed or what appears in their timelines.

The news comes after leaders of other social networks, like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk, have sparked backlash over sudden changes to popular apps like Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly Twitter). For years, Musk has drawn criticism for changing Twitter's hate speech policies through his X rebranding. And more recently, Zuckerberg this month defended Meta's decision to relax hate speech policies (permitting women to be called "property" and gay people to be called "mentally ill") by calling bans on such speech "out of touch with mainstream discourse."

© SOPA Images / Contributor | LightRocket

Lacework

Microsoft created a new engineering organization responsible for building its artificial-intelligence platform and tools, CEO Satya Nadella said in an email to employees Monday morning.

The new group will be led by Jay Parikh, Facebook's former head of engineering whom Nadella added to Microsoft's senior leadership team in October.

Microsoft is forming the group as it anticipates that AI, and particularly AI agents, will present a fundamental shift in how applications are built and used.

"2025 will be about model-forward applications that reshape all application categories," Nadella wrote in the email, which was also posted on Microsoft's blog. "More so than any previous platform shift, every layer of the application stack will be impacted. It's akin to GUI, internet servers, and cloud-native databases all being introduced into the app stack simultaneously. Thirty years of change is being compressed into three years!"

It said the new group, called CoreAI Platform and Tools, would include Microsoft's developer division and AI platform team and be responsible for building out GitHub Copilot. AI-related teams from the office of the chief technology officer, Kevin Scott, such as AI Supercomputer, AI Agentic Runtimes, and Engineering Thrive, would also be part of the new group.

Parikh worked at Facebook for more than a decade. He helped the company build out and maintain its massive technical infrastructure, a network of expensive data centers stocked with thousands of computers spanning several continents.

As one of Mark Zuckerberg's top lieutenants, Parikh also spearheaded various ambitious initiatives such as internet connectivity and an internet drone project that was eventually abandoned.

At Microsoft, Parikh's new reports include Eric Boyd, a corporate vice president of AI platform; Jason Taylor, a deputy CTO for AI infrastructure; Julia Liuson, president of the developer division; and Tim Bozarth, a corporate vice president of developer infrastructure.

The email said Parikh would also work closely with the cloud-and-AI chief Scott Guthrie; the experiences-and-devices leader Rajesh Jha; the security boss Charlie Bell; the consumer AI CEO Mustafa Suleyman; and Scott, the CTO.

Are you a Microsoft employee or someone else with insight to share?

Contact Ashley Stewart via email ([email protected]), or send a secure message from a non-work device via Signal (+1-425-344-8242).

Getty Images; Jenny Chang-Rodriguez/BI

Public records obtained by Business Insider reveal a Federal Trade Commission investigation into Publishing.com, a company that sells courses on creating AI-generated books.

The company, which was reported to have made nearly $50 million in 2022, charges $2,000 to teach customers how to generate books and e-books with help from ghostwriters and artificial-intelligence software. It's drawn scrutiny for its role in flooding Amazon with AI-generated content and has been the subject of numerous customer complaints alleging high-pressure sales tactics and difficulties getting refunds.

Investigations by the FTC often target companies suspected of duping consumers through deceptive marketing, hidden fees, or unfair refund policies. The agency can negotiate settlements and obtain fines and court orders that force businesses to change their practices or return money to customers.

Business Insider learned about the investigation through a public-contracts database that revealed the name of Publishing.com and showed the FTC had hired an expert witness. When BI contacted the FTC, it removed the company's name. A partially redacted scope-of-work statement confirmed the contract was for an investigation, though it offered no details about the investigation itself.

The FTC declined to comment.

When briefed on BI's reporting, two former FTC officials said that it was unusual for the FTC to budget tens of thousands of dollars for an expert witness unless the investigation was seen as viable. "They have to have a pretty good idea of what they want and what they want to establish," one former official said.

In 62 complaints to the agency obtained via the Freedom of Information Act, Publishing.com customers — including some who said they spent over $7,000 on courses and other materials — said the company sold them on the program during high-pressure sales calls, while obscuring how much money it would cost to make money from self-publishing books.

"They constantly say to use credit cards, borrow money, put yourself in debt in order to afford this program," one customer wrote in a complaint. Others said that refunds were difficult or impossible to obtain.

Publishing.com was founded in 2019 by the twin brothers Christian and Rasmus Mikkelsen. The company and its products have also gone by the names Publishing Life, Audiobook Income Academy, and AI Publishing Academy.

On social media and in news coverage, the 29-year-old Mikkelsens have described themselves as millionaire digital nomads who have cracked the secret to a hidden income stream.

On its website, the company shares positive social-media reviews and interviews with successful students, some of whom claim to have made more than six figures from self-publishing. In a disclaimer, the company says the average income of 1,119 students in a January 2024 survey was $1,801 a month — or $21,612 a year — in gross royalties.

After initially acknowledging BI's request for an interview, Publishing.com's chief operating officer, Michael Ohayon, did not respond to follow-up messages. The Mikkelsens did not respond to emails.

Vox wrote last year that the twins had helped drive an economy of low-value online slop. In 2018, Amazon briefly limited the twins' ability to sell on its platform after it learned they were running books through Google Translate and repackaging them for sale, Inc. magazine reported in a 2023 feature on the Mikkelsen twins. The story said Publishing.com was one of the fastest-growing companies in America.

Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images; Alex Wong/Getty Images; Aurelien Morissard/IP3/Getty Images; Chelsea Jia Feng/BI

The fusillade of major announcements from Meta this month — including the termination of its fact-checking and DEI programs and the ascension of its enigmatic content-moderation czar, Joel Kaplan, to head global policy — prompted a familiar churn of political reaction across the left and right. But virtually everyone agrees on one thing: Meta's changes are designed, at least in part, to please the incoming administration of Donald Trump.

That is why the most consequential announcement involves Joel Kaplan, Zuckerberg's tight-lipped political consigliere. For the coming years, Kaplan will be the face in your living room, justifying Meta's handling of whatever crisis, catastrophe, or hypocrisy the new Trump era is likely to ring in. He will speak at Davos, before committees, and on "Good Morning America," defending Meta publicly — and Mark Zuckerberg personally — from the right, the left, and quite possibly from Trump himself.

Kaplan is not widely known. Yet he arguably has done more to shape the modern internet — and quicken its consolidation with and capture of American politics — than any non-CEO in the world. With his ascension to the chief policy position at Meta, Kaplan etches his name into the pantheon of great political actors on the Washington stage — akin to a combination of Rahm Emanuel and Henry Kissinger, if they'd had every major global tech CEO on speed dial.

You can understand Kaplan's value to Meta by appreciating the two dimensions that account for his rise: Kaplan as the talented political fixer, and as the free-speech intellectual. Two distinct stories capture both dimensions of Kaplan's impact on Meta and on Zuckerberg.

Months before Trump was suspended from Facebook in 2021 following the attack of January 6, Trump's account was very nearly curtailed in an entirely separate ordeal. During the George Floyd protests and riots of 2020, Trump wrote a message on Facebook that ignominiously warned, "When the looting starts, the shooting starts." Per Facebook's rules, which prohibit incitement to violence, Trump's post possibly merited a takedown.

For Meta, this was a problem from hell. Not removing Trump's post would inflame liberal America. Removing it would enrage conservatives — not to mention the sitting president, who just days before had threatened to punish Meta for its alleged anti-conservative bias.

Then something miraculous happened: Trump called Zuckerberg. As Zuckerberg would tell it — mirroring a version later to be widely retold — Trump called Zuckerberg to plead his case, while Zuckerberg lectured Trump about using the platform responsibly. Hours later, another miracle followed: Trump wrote a follow-up post to finesse his point, quelling the discord.

The crisis was averted. Equally important, however, was the supposed lesson of this story: Trump — desperate to keep his account intact — needed Meta.

This story has been broadly reported. But stories that involve Kaplan tend to have a carefully hidden trap door.

As it turned out, there was a problem with this account: It was precisely backward. In the early morning of May 29, 2020, White House staffers gathered around on speakerphone and listened in disbelief to the voice on the other end: It was Mark Zuckerberg — calling them, at Kaplan's arrangement — asking for a personal word with Trump. Those familiar with this call would later say Zuckerberg's request was tinged with vulnerability, as he and Kaplan, also on the call, described the inevitable liberal revolt at Meta's headquarters if something weren't done about Trump's post. "I have a staff problem," Zuckerberg explained, according to those with knowledge of the call. (Meta has previously denied Zuckerberg said anything to this effect, maintaining that Zuckerberg was unequivocal in condemning the post.) When Trump rang Zuckerberg's cell later that afternoon, it wasn't contrition he was showing Zuckerberg — it was a favor.

A decade ago, the chasm separating Zuckerberg and Trump seemed as insurmountably wide as that between the Capulets and the Montagues. Yet the two men have spent years running toward each other.

This story, and its turns, illuminates several key things. First, it suggests the lengths Meta will go to convince the public that Trump — just like its 3 billion users — was dependent upon Meta for relevance. It shows the cunning of Kaplan in finding a way to project that image — through a half story that was widely repeated in official Washington — while simultaneously defusing a serious crisis (Kaplan had put out a "four-alarm fire," one of his former staffers previously told me).

Above all, it illustrates the dependency that animates Zuckerberg and Trump's relationship, and hints at what direction it runs in: Meta needs Trump — perhaps a lot more than Trump needs Meta.

For much of his life, Kaplan has played exactly this sort of role: attendant lord and advisor to princes. After finishing at the top of his class at Harvard Law School and serving as an officer in the Marine Corps, Kaplan clerked for Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia; played a pivotal role in the events leading to Bush v. Gore; and became a senior advisor to George Bush during all eight years. He was among the closest advisors to his longtime friend Brett Kavanaugh, counseling the judge at the darkest hour of his confirmation fiasco.

But it's his role serving Zuckerberg that is the male relationship that defines Kaplan's professional life and achievements. Since joining Meta in 2011, Kaplan has helped navigate Zuckerberg's path and entry into official Washington. Initially, that entailed accompanying a young Zuckerberg to President Barack Obama's Oval Office, or overseeing Zuckerberg's preparation for congressional hearings. But with the explosion of MAGA, Kaplan's role grew dramatically, charting a path that would bring Zuckerberg and a fast-changing Republican Party into something resembling — if not goodwill — then a mutual accord.

Half of this Zuckerberg achieved himself, by slotting Kaplan into a major role overseeing content moderation. But the human side of Washington — never Zuckerberg's strong suit — was Kaplan's métier: arranging Oval Office huddles with Zuckerberg and Trump, or organizing a series of private dinners with mostly conservative (and some liberal) influencers. Kaplan, as Meta staffers and Washington Republicans told me, made sure that MAGA Republicans knew they always had a seat at Zuckerberg's proverbial table. (Meta did not provide new comment for this story.)

This growing authority inside Meta left many idealist staffers convinced of Kaplan's thralldom to conservative ideology. But Kaplan is also beloved and defended by many Democrats at Meta and throughout Washington — a fact that explains, in part, Meta's successful evasion of any significant tech regulation during the Biden presidency.

And yet Kaplan's most remarkable achievement is playing out right now: the extraordinary — once unthinkable — political romance between Mark Zuckerberg and Donald Trump. A decade ago, the chasm separating these individuals seemed as insurmountably wide as that between the Capulets and the Montagues. Yet the two men have spent years running toward each other, barreling through and against the gauntlet of their respective tribes: Zuckerberg through the leftist principles of the Bay, Trump through Republican Washington.

In this slow-motion marriage plot, Joel Kaplan is their Friar Laurence, bringing his artful guile and influence to bear in the improbable effort to knit their two families together. Kaplan has "helped make sure the ties were never irrevocably broken — even through Trump being deplatformed," observes Katie Harbath, a Republican who served as public policy director under Kaplan for a decade and who now heads the tech consulting firm Anchor Change. "Joel was sort of the captain of that ship."

Beginning with Trump's rise in 2016, Kaplan grew into another significant role: a de facto superintendent of the platform's rules around speech and content moderation. It's in this role — as a legal intellectual offering a distinct philosophy of free expression — that colleagues say Kaplan has shaped the company publicly, and Zuckerberg personally.

It was Kaplan, for example, who appeared on Fox News last week to explain the end of the fact-checking program, characterizing the decision as an effort to "reset the balance in favor of free expression." This echoed Zuckerberg's own video announcement, in which he lamented that the program had become "just too politically biased."

Samuel Corum/Getty Images

These comments are of a piece with Kaplan's own philosophy on free expression, which colleagues have summed up in the adage by Justice Louis Brandeis: that the remedy for false or misleading speech isn't "enforced silence," but instead "more speech."

It is tempting to view the complex issues at Meta as a simple proxy battle between "pro" and "anti" free expression. The fact-checking program was not without errors, as any complex program will be. And it is a genuine win for free expression that restrictions on user speech — on topics such as immigration, or gender and sexuality — are now lifted. Same for the nixing of DEI programs, which too often function to manufacture consensus on live issues at the internal staff level.

But the truth is there have long been meaningful objections to Kaplan's — and increasingly Zuckerberg's — Brandeisian "more speech" rationale that Meta so often proffers for its decisions.

The first is that, when it comes to political expression, the basis for Meta's decisions often manifests not as high principle, but as political expediency.

The fact-checking program is a case in point. Few programs were so vocally targeted — and fervently manipulated — by conservative critics. For any conservative media publisher dinged for misinformation by Meta's algorithm, Kaplan's cellphone effectively functioned as a personalized, interlocutory appeals process. Such was the case with articles by Breitbart, or the Instagram posts of Charlie Kirk, who successfully appealed to Kaplan to intervene, and to have their flags or strikes removed. Or in the case of Meta's filter against "Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior," which Kaplan and other executives quickly froze, around the time they learned that its classifier had begun flagging posts from The Daily Wire and Sinclair.

The second problem is that Kaplan's defenders have fallen under a common misreading of Brandeis. Unlike Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., his fellow Supreme Court justice— who generally prized individual autonomy — Brandeis believed the ultimate purpose of free expression was the preservation of democratic self-government itself. The reason "more speech" offers an effective remedy is that, in Brandeis' view, the freedom of unlimited speech was inextricably married with duty: what he called "the political duty of public discussion." Duty is a word that generally conveys the foregoing of certain liberties, to achieve a higher purpose. The Brandeisian view, in essence, described the First Amendment as a kind of bargain struck with Americans at large: In exchange for a near-bottomless freedom to purvey unlimited speech, Americans accepted an implied duty to yield to the necessary prerogatives of well-ordered public discussion.

Yet under Kaplan's Policy team, content decisions at Meta consistently tacked away from Brandeis' view. Perhaps no controversy illustrates the point better than a project called Common Ground.

A silver lining to Meta's termination of fact-checking is it may clarify a new consensus that recognizes the futility of the agonizing efforts of the past 10 years attempting to liberalize social media.

Conceived by Meta staff in response to the 2016 election, Common Ground was a proposal to remake Facebook into a forum for healthier public discussion. In a bundle of proposed algorithm changes — detailed in internal memos — the program would replace users' self-segregation with more "exposure to cross-cutting viewpoints," downplay "incivility," recommend that users join more politically diverse groups, and boost news outlets with high bipartisan readership.

Though perhaps idealistic-sounding, Common Ground was not a left-wing chimera. In fact, its premise was drawn in part from the research of the New York University psychologist Jonathan Haidt — a famously vocal critic of progressive ideology in college campuses and workplaces — whose findings Meta staffers had studied rigorously. It was precisely the sort of project that would make liberals more likely to encounter, say, a Wall Street Journal op-ed article opposing mask mandates.

Kaplan and his team, however, correctly sensed that such proposals — no matter how "nonpartisan" in fact — would be castigated as partisan in appearance. In internal review sessions, Kaplan's team raised its concerns that the proposal would have a disparate effect on conservative users.

But the true killer lurked in a crucial detail: Exposure to this more ennobled strain of public discussion tended to reduce the engagement that users had with the platform. In a business model in which enragement equals engagement, it turns out, Brandeisian discussion is an unwarranted expense.

Kaplan's defenders backstop these choices with a common refrain: Kaplan's team has ensured Meta's content policies remain "defensible." By "defensible," Meta staffers intend to invoke the importance of public accountability. What they tend to mean, though, is policies that can adequately be explained during a grilling before Congress — an understandable concern for a company that's been hauled before Congress more than 30 times.

That is perfectly plausible reasoning. But one thing it certainly isn't is a vindication of First Amendment values — a bulwark in the Constitution whose singular purpose, after all, is to prevent meddling by Congress, and government generally. Zuckerberg now says he regrets caving to pressure from the Biden administration during the COVID pandemic. But does anyone doubt that, the next time Trump calls Zuckerberg, the CEO won't be all ears? (Just as he was avidly listening when Jared Kushner similarly pressured Zuckerberg in 2020, arm-twisting repeatedly to cooperate with Trump's COVID response.) Kaplan is there to ensure the message, even if not followed upon, gets through loud and clear.

Putting a chief Washington lobbyist largely in charge of speech policy may be politically savvy. But it is the opposite of how a company would take seriously its obligations to free expression — an invitation, essentially, to a Republican Congress, or a Democratic White House, to inject politicians' notions about public discourse into your news feed. "One thing I notice," Harbath notes thoughtfully, "is that after every major election since 2016, Mark has done this big recalibration about how the company handles content, based upon the electoral results."

Critics of Kaplan's supposed right-leaning bias, then, miss the point. It's that Kaplan and Zuckerberg's commitment to Brandesian free expression, as Gandhi might say, would make for an excellent idea. And some of Meta's changes — relaxing the restrictions on immigration and gender — are indeed aligned with liberal principles of free expression. But unavoidably, the platform remains a Death Star of bad reasoning, amplifying the worst of the left and right. Nor would Brandeis recognize Kaplan's enthusiasm for the incoming President Trump and his administration as "big defenders of free expression" — a man who sues local newspapers as retribution for polls, publicly invites violence on journalists, and suggests the US military shoot protesters for exercising their First Amendment rights — perhaps the most anti-First Amendment candidate for president since Woodrow Wilson. Both on the platform and off, Meta's commitment reflects the opposite of Brandeis' well-ordered public discussion: a world of all freedom, and no duty.

One silver lining to Meta's termination of fact-checking, then, is that it has the potential to clarify a new consensus: one that recognizes the futility of the agonizing efforts of the past 10 years attempting to liberalize social media — as fruitless and naive as environmentalists who implore oil and gas companies to cease being oil and gas companies. Scholars such as Yuval Noah Harari and Jonathan Rauch have separately argued that social media at scale is inherently inimical to liberal values — and that its mob-like pathologies, with its viral lies and conspiratorial reasoning, eerily resemble the same tendencies of pre-Enlightenment, medieval Europe.

That sort of tragedy can be laid at the feet only of generations, not individuals. And that is the deep and common bond that Zuckerberg and Trump share. Both are men whose vast seizure of power was made possible by the energy and unique pathology of the mob — allowing one to build a company, the other a political movement — as they leveraged its bizarre vise grip on our attention along with the mob's enduring ability, as Holmes warned, to "set fire to reason." In bringing these men to power, the best and brightest of their generation — Joel Kaplan, Sheryl Sandberg, Peter Thiel, and Elon Musk, nearly all the same age — ushered in a new strain of faithlessness, turning social media into a prison, and making our public life a hostage of the internet.

Zuckerberg and Kaplan's announcement is not an embrace of the right, or repudiation of the left. It's another example of what Meta does too often: wrap its business and political decisions into the language of liberal values and free expression. In reality, Meta does have a clear policy around free expression — but it doesn't follow the philosophical quotations of Louis Brandeis, or Oliver Wendell Holmes. Rather, under Zuckerberg and Kaplan, Meta's North Star will always faithfully resemble the old chestnut from Lyndon B. Johnson: "Power is where power goes."

Benjamin Wofford has written for Wired, Politico Magazine, Vox, and Rolling Stone, and is a graduate of Stanford Law School.

picture alliance/Getty Images

Mark Zuckerberg has shown himself to be the ultimate Silicon Valley shapeshifter, and in the first couple weeks of 2025, we got our best look yet at the latest version of the Meta CEO.

To kick off the new year, Zuckerberg made some big changes at his company, including ditching third-party fact-checking and slashing DEI initiatives.

He appears to be remaking Meta, which did not respond to a request for comment from Business Insider, at least partly in the image of Donald Trump and Elon Musk. And he doesn't seem too concerned about the backlash he's facing in some quarters, including from the same people who villainized him during the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the 2016 election, or even his own Meta employees — many of whom have reacted negatively to his latest decision to roll back DEI efforts.

His recent moves hint that he's entering a new era, one in which his leadership increasingly reflects Trump's tastes.

For years, Zuckerberg was known as an almost robotic presence in Silicon Valley. Some people criticized him for copying ideas rather than innovating, and others held onto his image as a wunderkind wearing hoodies or too much sunscreen.

By the end of 2023, though, the Meta CEO had undergone a substantial makeover and was garnering praise in business and cultural circles.

Zuck got shredded and was winning jiu-jitsu competitions. He went on popular podcasts, like Joe Rogan's, to discuss his workouts and make fun of himself.

As a business leader, he acted as the adult in the room and led Meta's "year of efficiency," which turned the company's stock around.

In 2024, he continued his transformation: He ditched his jeans and hoodie uniform for designer T-shirts and gold chains. And his adoration for his wife Priscilla Chan — as evidenced through gifts like a statue of her, a custom Porsche minivan, and his very own version of "Get Low" — won him fans.

His newfound swagger grew into a new kind of boldness.

In the fall of last year, he said his biggest regret in his two decades of running Meta was taking responsibility and apologizing for problems that he believed weren't Meta's fault.

Cut to 2025. Zuckerberg now appears to embrace some of the "anti-woke" ideas favored by some political billionaires like Musk, Peter Thiel, and, of course, Trump.

While Zuckerberg didn't endorse Trump — or Harris — in the 2024 election, he and other tech CEOs were quick to congratulate Trump on his victory. Zuck met with Trump at Mar-a-Lago weeks after the election and, through Meta, donated $1 million to his inaugural committee.

Now, he's taking what he calls "masculine energy" and putting it into action at Meta.

"Masculine energy, I think, is good, and obviously society has plenty of that, but I think that corporate culture was really trying to get away from it," he said in an interview on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast that aired on Friday. "It's like you want feminine energy, you want masculine energy."

"But I do think the corporate culture sort of had swung toward being this somewhat more neutered thing," he added.

He started the new year by putting Dana White, the UFC CEO and Trump's longtime ally, on Meta's board and replacing the company's head of policy, liberal Nick Clegg, with former GOP lobbyist Joel Kaplan.

Sean M. Haffey

Then, he ended third-party fact-checking on Meta platforms, which some conservatives have criticized, in favor of a more hands-off approach. Like X, Meta will now use "community notes" to allow users to police each other.

"The recent elections feel like a cultural tipping point towards, once again, prioritizing speech," Zuckerberg said while announcing the changes, implying that the choice was, at least in part, a response to the political landscape.

Meta's CMO, Alex Schultz, also told BI that Trump's election influenced the policy change.

The decision has come under scrutiny, with some saying the lack of content moderation opens the door to hate speech.

Under the policy, Meta users can say that members of the LGBTQ+ community are mentally ill for being gay or transgender, for example.

Dozens of fact-checking organizations have signed a letter calling it "a step backward for those who want to see an internet that prioritizes accurate and trustworthy information."

Still, others, including Musk and Trump, lauded the change.

"Honestly, I think they have come a long way, Meta, Facebook," the president-elect said on Tuesday.

In the recent Rogan interview, Zuckerberg said while some may see the timing of the content changes as "purely a political thing," it's something he has been thinking about for a while.

"I feel like I just have a much greater command now of what I think the policy should be and like, this is how it's going to be going forward," Zuckerberg said.

Zuckerberg's recent decision to cut Meta's DEI initiatives could also placate conservatives, who have criticized such policies.

While Trump has not commented on the DEI decision, he has criticized DEI policies in the past.

On Friday, Meta's vice president of human resources, Janelle Gale, said in an internal memo that the company would no longer have a team focused on DEI or consider diversity in hiring or supplier decisions.

"The legal and policy landscape surrounding diversity, equity and inclusion efforts in the United States is changing," she said in a memo.

The decision sparked a backlash among some. Internally, nearly 400 employees reacted with a teary-eyed emoji to the announcement; one called it "disappointing," and another said it was a "step backward," BI reported on Friday.

"Wow, we really capitulated on a lot of our supposed values this week," another employee commented, seemingly referring to both the DEI and fact-checking moves.

Others, though, did seem to support the move: 139 employees "liked" the post, and 57 responded with a heart emoji.

Meta has reportedly ended diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs that influenced staff hiring and training, as well as vendor decisions, effective immediately.

According to an internal memo viewed by Axios and verified by Ars, Meta's vice president of human resources, Janelle Gale, told Meta employees that the shift was due to "legal and policy landscape surrounding diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in the United States is changing."

It's another move by Meta that some view as part of the company's larger effort to align with the incoming Trump administration's politics. In December, Donald Trump promised to crack down on DEI initiatives at companies and on college campuses, The Guardian reported.

© Bloomberg / Contributor | Bloomberg

In the wake of Meta’s decision to remove its third-party fact-checking system and loosen content moderation policies, Google searches on how to delete Facebook, Instagram, and Threads have been on the rise. People who are angry with the decision accuse Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg of cozying up to the incoming Trump administration at the expense […]

© 2024 TechCrunch. All rights reserved. For personal use only.

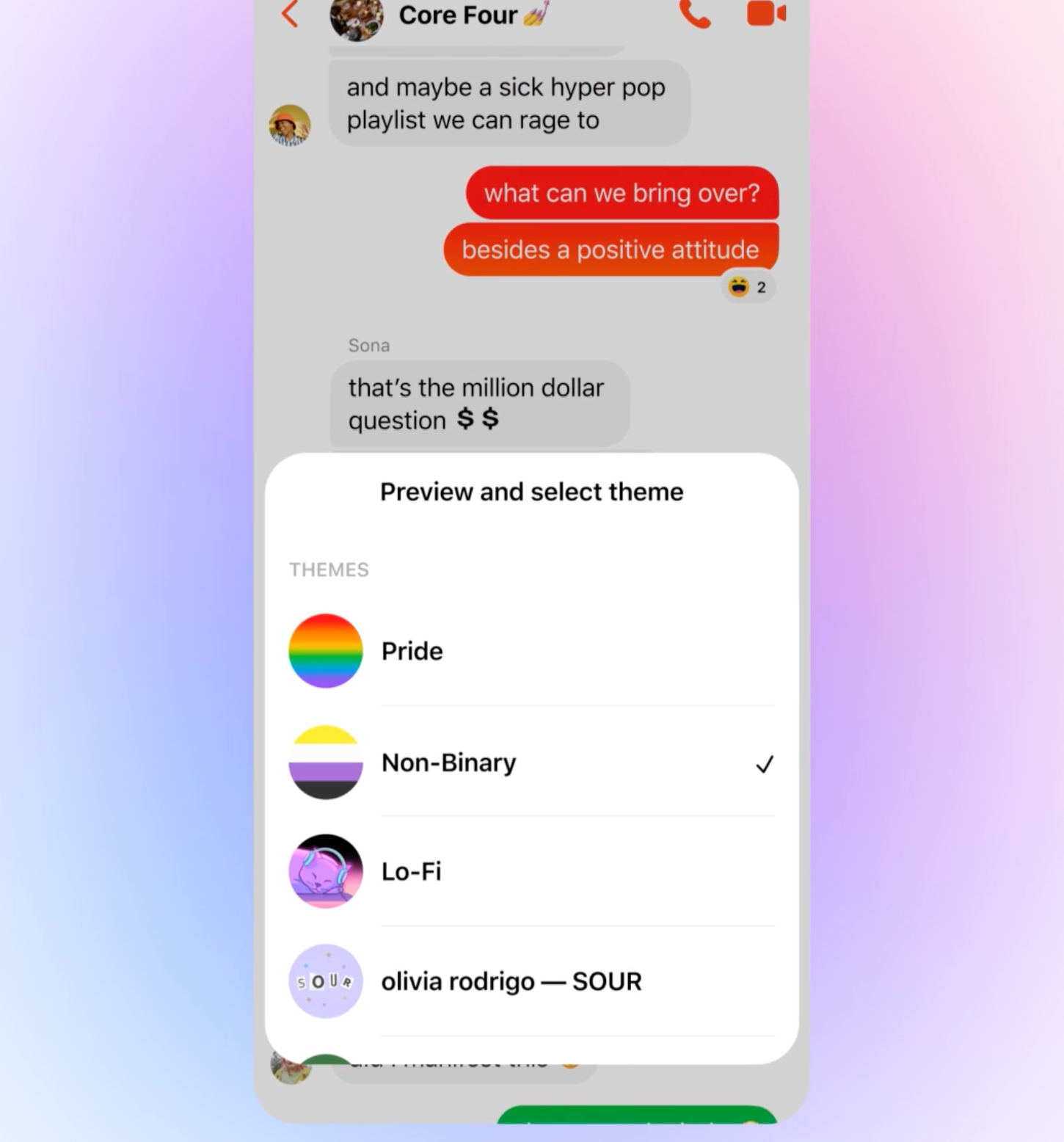

Meta deleted nonbinary and trans themes for its Messenger app this week, around the same time that the company announced it would change its rules to allow users to declare that LGBTQ+ people are “mentally ill,” 404 Media has learned.

Meta’s Messenger app allows users to change the color scheme and design of their chat windows with different themes. For example, there is currently a “Squid Game” theme, a “Minecraft” theme, a “Basketball” theme, and a “Love” theme, among many others.

These themes regularly change, but for the last few years they have featured a “trans” theme and a “nonbinary” theme, which had color schemes that matched the trans pride flag and the non-binary pride flag. Meta did not respond to a request for comment about why the company removed these themes, but the change comes right as Mark Zuckerberg’s company is publicly and loudly shifting rightward to more closely align itself with the views of the incoming Donald Trump administration. 404 Media reported Thursday that many employees are protesting the anti LGBTQ+ changes and that “it’s total chaos internally at Meta right now” because of the changes.

The trans theme was announced for Pride Month in June 2021, and the nonbinary theme was announced in June 2022 in blog posts that highlighted Meta’s apparent support for trans and nonbinary people. Both of these posts are no longer online. Other blogs about updates to Messenger have been moved over from the old website they were originally published on to new URLs on the Meta newsroom, but these two blog posts have not.

“This June and beyond, we want people to #ConnectWithPride because when we show up as the most authentic version of ourselves, we can truly connect with people,” the post announcing the trans theme originally said. “Starting today, in support of the LGBTQ+ community and allies, Messenger is launching new expression features and celebrating the artists and creators who not only developed them, but inspire us each and every day.”

Meta employees are furious with the company’s newly announced content moderation changes that will allow users to say that LGBTQ+ people have “mental illness,” according to internal conversations obtained by 404 Media and interviews with five current employees. The changes were part of a larger shift Mark Zuckerberg announced Monday to do far less content moderation on Meta platforms.

“I am LGBT and Mentally Ill,” one post by an employee on an internal Meta platform called Workplace reads. “Just to let you know that I’ll be taking time out to look after my mental health.”

On Monday, Mark Zuckerberg announced that the company would be getting “back to our roots around free expression” to allow “more speech and fewer mistakes.” The company said “we’re getting rid of a number of restrictions on topics like immigration, gender identity, and gender that are the subject of frequent political discourse and debate.” A review of Meta’s official content moderation policies show, specifically, that some of the only substantive changes to the policy were made to specifically allow for “allegations of mental illness or abnormality when based on gender or sexual orientation.” It has long been known that being LGBTQ+ is not a sign of “mental illness,” and the false idea that sexuality or gender identification is a mental illness has long been used to stigmatize and discriminate against LGBTQ+ people.

Earlier this week, we reported that Meta was deleting internal dissent about Zuckerberg's appointment of UFC President Dana White to the Meta board of directors.

A security researcher found a bug in a Facebook ad platform, which gave him access to the company’s internal infrastructure.

© 2024 TechCrunch. All rights reserved. For personal use only.

Google searches for how to cancel and delete Facebook, Instagram, and Threads accounts have seen explosive rises in the U.S. since Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced that the company will end its third-party fact-checking system, loosen content moderation policies, and roll back previous limits to the amount of political content in user feeds. Critics see […]

© 2024 TechCrunch. All rights reserved. For personal use only.