'I don't like this Musk chap': Reform members say they're unbothered by spat

Photo by Viktor Fridshon/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Russian forces are using explosive-packed drones connected to their operators by fiber-optic cables to deliver unjammable precision strikes on Ukrainian troops and military equipment, and Kyiv is looking for a fix to fight back.

Fiber-optic drones have been increasingly appearing in combat over about the last year, and they're a challenge. These drones are dangerous because they can't be jammed with traditional electronic warfare and are difficult to defend against, highlighting the need for a solution.

The drones are "a real problem" because "we cannot detect and intercept them" electronically, Yuriy, a major in an electronic-warfare unit of the Ukrainian National Guard, told Business Insider. "If we can see, we can fight."

The problem is one that the defense industry is looking into closely. Kara Dag, for instance, is an American-Ukrainian technology company that's developing software and hardware to defend against Russian drones for the military and working on a solution, but it's still early days.

The company's chief technology officer, who goes by the pseudonym John for security purposes, said the ongoing conflict is a "war of drones." He told BI Ukraine had managed this fight well with jamming techniques, but Russia has found ways to slip past some of its defenses.

Fiber-optic drones, which Russia appears to have started flying into battle last spring, are first-person view, or FPV, drones, but rather than rely on a signal connection, they are wired with cables that preserve a stable connection. As a result, these drones are resistant to electronic warfare, like radio frequency jammers, and produce high-quality video transmissions.

Russian Defense Ministry Press Service via AP

In August, combat footage from Russian fiber-optic drones began to circulate, indicating a more lasting presence on the battlefield. Now, both militaries are using these drones.

Fiber-optic drones are highly dangerous, John said, as they can fly in tunnels, close to the ground, through valleys, and in other areas where other drones might lose connection with their operators. They are also tough to detect because they don't emit any radio signals.

Russia can use these drones to destroy Ukrainian armored vehicles and study its defensive positions, he said. Since they don't have bandwidth problems, these drones "can transmit very high-quality picture and they literally see everything."

The drones aren't without their disadvantages, though. Yuriy shared that the fiber-optic drones are slower than the untethered FPV drones and unable to make sharp changes in direction. He said that Russia does not have too many of these drones, either, nor does it use them in every direction of the front lines. But where they are used, they're a problem.

Because jamming doesn't work on fiber-optic drones, there are efforts underway to explore other options for stopping these systems, such as audio and visual detection. But this kind of technology can be expensive and hard to manufacture.

Photo by Viktor Fridshon/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

John said that the company has developed a low-cost solution to find fiber-optic drones. One element of this system is an array of dozens of microphones that can be focused on one point in the sky to listen for any nearby drones. The second element is an unfocused infrared laser that highlights any object in a certain area of the sky while a camera records any reflected light coming back.

It's a single device that can be placed around a kilometer from troop positions. John said the device is in lab testing, and the next step is to deploy it in real combat conditions on the front lines next month. The plan is to eventually produce several thousand of these devices every month.

The introduction of fiber-optic drones into battle — and Ukraine's subsequent efforts to counter them — underscores how both Moscow and Kyiv are constantly trying to innovate with uncrewed systems before the enemy can adapt, a trend that has been evident throughout the war.

In a previous interview with BI, Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine's minister of digital transformation, described the technology and drone race playing out in this fight as a "cat-and-mouse game." He said that Kyiv is trying to stay several steps ahead of Moscow at all times.

The Ukrainian military said last month that it was testing fiber-optic drones, adding that "FPV drones with this technology are becoming a big problem for the enemy on the front line."

On Tuesday, a Ukrainian government platform that facilitates innovation within the country's defense industry shared new footage of fiber-optic drone demonstrations on social media. Russia, if it's not already, may soon find itself working to counter these new drones as well.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/the-wall-of-winnipeg-and-me-the-jock-plays-well-with-others-010825-2352dd376bac486e89b9bc759ecf508f.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/honeymoon-suite-010825-2d8ec0c1f46c4e528dd1b54d78b84152.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/Rory-Callum-Sykes-LA-Fires-011124-03-0a62ab9e95bd4dbab91e347eccc9ccf9.jpg)

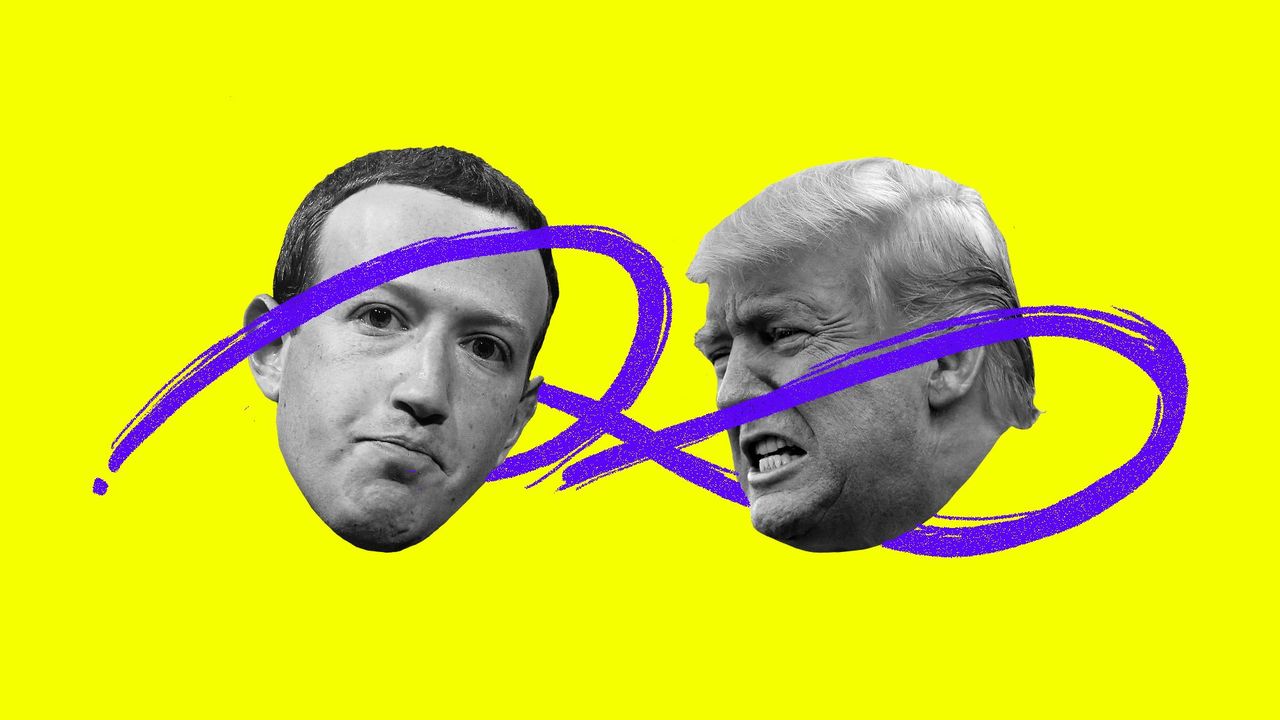

They say it's hard to turn a battleship around, but Mark Zuckerberg just about-faced his globe-spanning, $1.5 trillion-value, 3 billion-user company — transforming Meta from a bastion of Silicon Valley's socially progressive neoliberalism into a full-on MAGA hive.

Why it matters: After Zuckerberg's embrace of Trump and Trumpism, Silicon Valley is holding its breath to see whether a whole row of tech dominoes is about to fall in the same direction.

Some early signs of wobble:

State of play: So far, while Meta's competitors have ritualistically expressed their willingness to work with the new administration, none of them has gone as far as Zuckerberg in donning the corporate equivalent of a MAGA hat.

Publicly traded companies with billions of customers generally try not to alienate any large bloc of the public. Becoming closely aligned with either side of the U.S.'s red/blue divide risks limiting a business's market reach.

Yes, but: Zuckerberg, unlike his rival CEOs, has absolute voting control of his company.

Case in point: Apple has always aimed, and often managed, to transcend mere politics and inhabit a separate dimension making "great products that people love."

This time around, these firms are quietly signaling they want to cooperate with the new Trump team on issues — like competition with China — where they see common ground.

During the first Trump term, an activist young tech work force occasionally took to the barricades to protest government policies and pressure reforms from their employers.

What we're watching: With each fresh controversy the new administration touches off, tech CEOs will have to navigate a maze involving Trump's demands for loyalty, employees' emotions and wishes, and their own strategies.

The bottom line: Trump used to say that Zuckerberg would "spend the rest of his life in prison." But the incoming president's relationships with business leaders are strictly transactional, and Meta's CEO is probably resting a lot easier now.

Twelve years ago, I could have told you exactly what happened at my first CES and what happened at my third. Each was a chapter with a beginning, middle, and end; the lines between them drawn clearly. But now, 15 years since I attended my first CES, it’s a lot fuzzier. I know I missed my flight home at that first show. I know I saw a lot of cameras at first, and then progressively fewer cameras over the years. I know there were team dinners and early meetings, but I couldn’t tell you what happened when.

What I do know about my first CESes is that I had — and I cannot stress this enough — no clue what I was doing. The same went for CES two, three, and four, to varying degrees. I think I had a Pentax DSLR loaned to me by a colleague. I had a work-issued BlackBerry and, I’m pretty sure, insisted on wearing nice dresses and impractical shoes to evening events. There was no Uber at the beginning, and you could spend an hour waiting in a cab line at the airport. We stayed at the MGM Grand, which housed live lions at the time.

I broke an 11-year streak of not going to CES this year, which gave me a rare opportunity. It’s not often in life that we get to step back and see something...

Aubrey Plaza and Jeff Baena were collaborators—both in their onscreen work and in their life together off-camera.

But on Jan. 3, the actress’s filmmaker husband died by suicide at the age 47,...

Aubrey Plaza and Jeff Baena were collaborators—both in their onscreen work and in their life together off-camera.

But on Jan. 3, the actress’s filmmaker husband died by suicide at the age 47,...