Have we finally solved mystery of magnetic moon rocks?

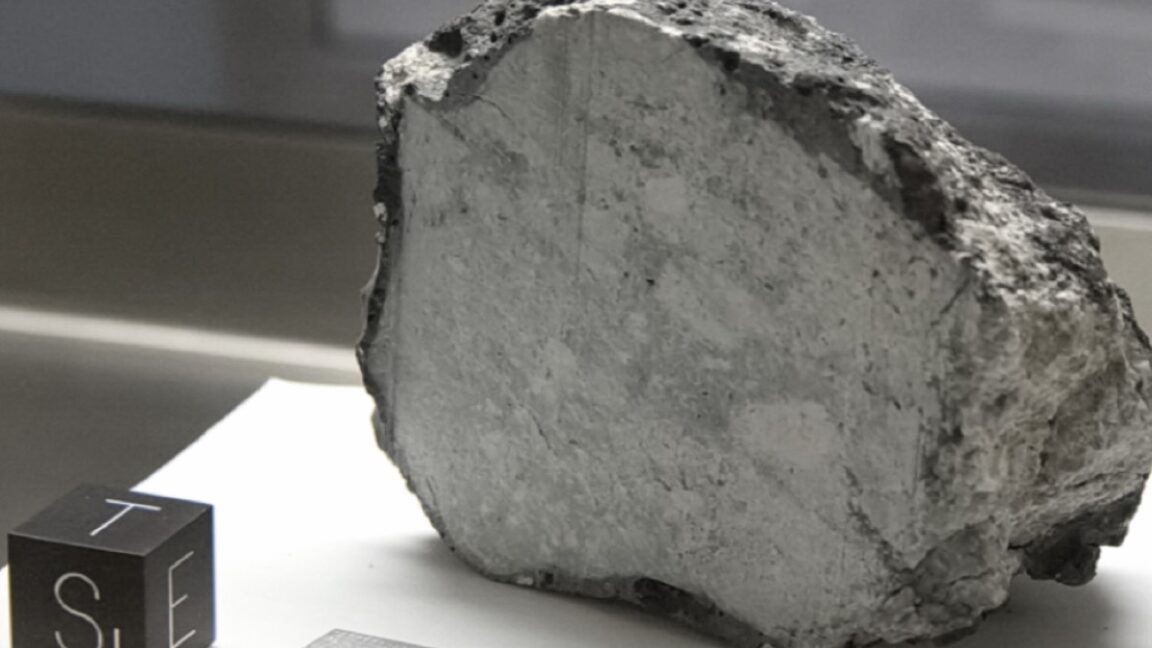

NASA's Apollo missions brought back moon rock samples for scientists to study. We've learned a great deal over the ensuing decades, but one enduring mystery remains. Many of those lunar samples show signs of exposure to strong magnetic fields comparable to Earth's, yet the Moon doesn't have such a field today. So, how did the moon rocks get their magnetism?

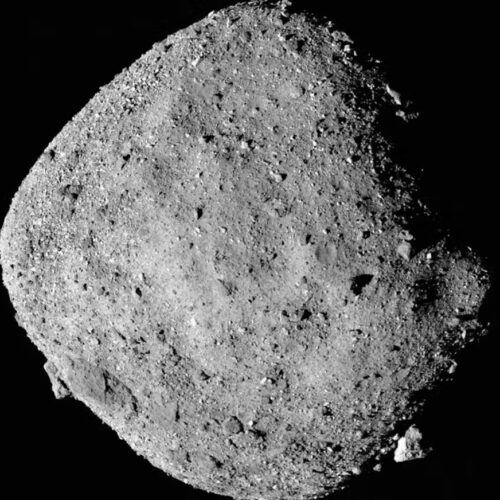

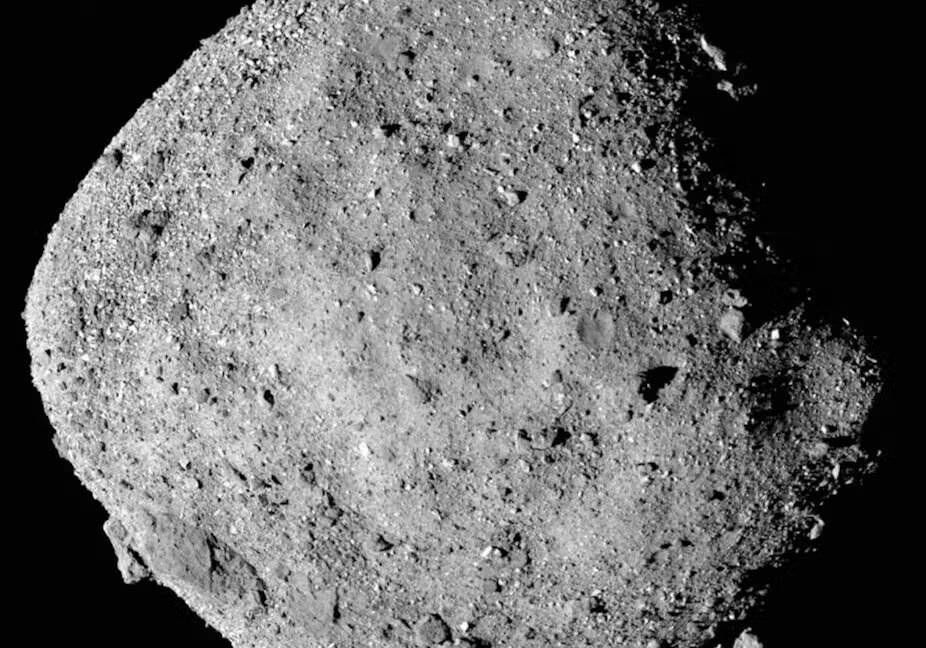

There have been many attempts to explain this anomaly. The latest comes from MIT scientists, who argue in a new paper published in the journal Science Advances that a large asteroid impact briefly boosted the Moon's early weak magnetic field—and that this spike is what is recorded in some lunar samples.

Evidence gleaned from orbiting spacecraft observations, as well as results announced earlier this year from China's Chang'e 5 and Chang'e 6 missions, is largely consistent with the existence of at least a weak magnetic field on the early Moon. But where did this field come from? These usually form in planetary bodies as a result of a dynamo, in which molten metals in the core start to convect thanks to slowly dissipating heat. The problem is that the early Moon's small core had a mantle that wasn't much cooler than its core, so there would not have been significant convection to produce a sufficiently strong dynamo.

© OptoMechEngineer/CC BY-SA 4.0