Trump's Post Office plan has a $400 billion conundrum

Who's going to be left holding the $400 billion bag? That's the ultimate question that undergirds the debate over the future of the post office.

Why it matters: The U.S. Postal Service suffers under a system of pension obligations that is seen at no private company and in no other government department.

- But there's also historically been no appetite in Congress to fix this longstanding problem.

Driving the news: The White House on Friday denied a Washington Post report that President Trump intended to dissolve the USPS board and take control of the Post Office — but Trump did say that he wanted some kind of Commerce Department "merger" that would ensure the agency "doesn't lose massive amounts of money."

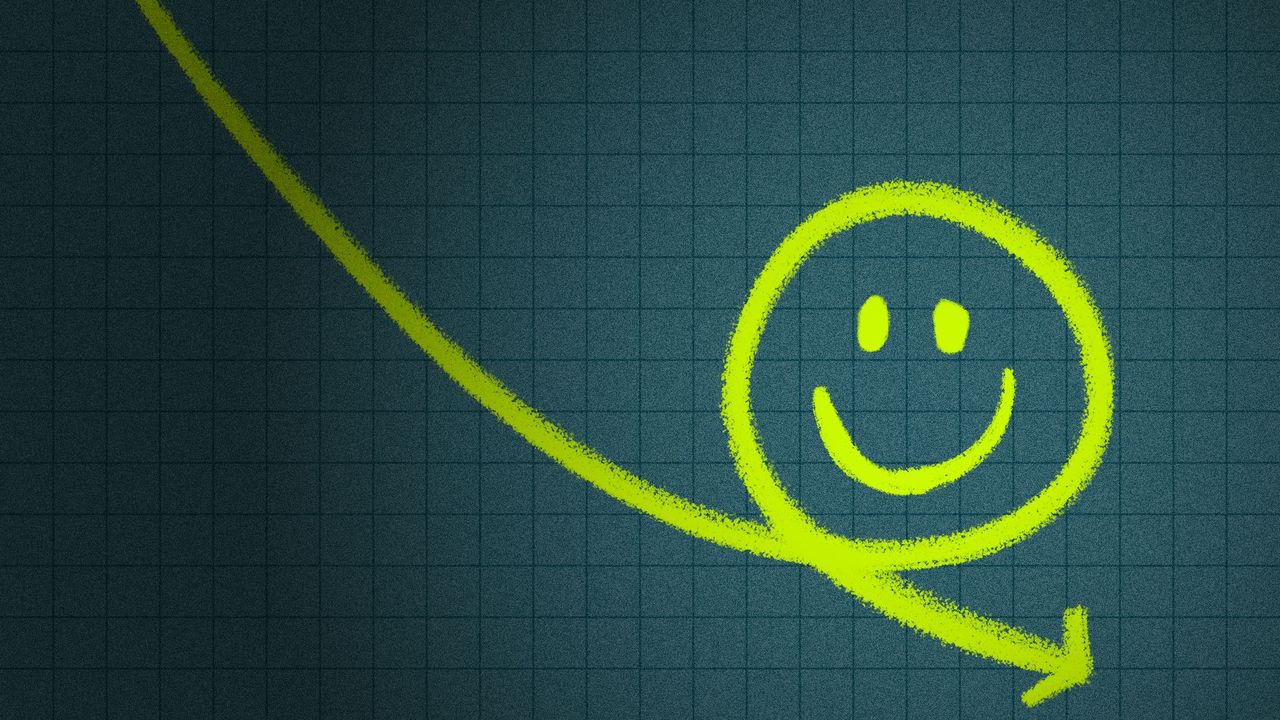

The big picture: Per a comprehensive report that was released last year by the USPS inspector general, the Post Office ended fiscal year 2022 with pension and healthcare liabilities of $409 billion — against assets of just $290 billion.

- Retirement costs alone make up about 12% of the USPS's total expenses — but the Post Office has no control over where that money goes, how it's invested, or how it's disbursed.

By the numbers: The Post Office has more than 700,000 retirees and survivors collecting benefits — and employs more than 500,000 people who will collect pensions in the future.

- The agency pays $10 billion per year into federal pension programs it doesn't control.

- That money is invested extremely conservatively, with a 100% allocation to Treasury bonds. As a result, the funds actually lost money, in real terms, in both the 2021 and 2022 fiscal years.

- According to the inspector general's report, the $155 billion deficit in the Post Office's retirement funds at the end of fiscal 2021 would have been a $963 billion surplus if that money had been invested in a standard portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds since inception.

The intrigue: Other federal agencies receive money from Congress to make required employer contributions; the Post Office doesn't.

- Private pension plans, and even some government plans, including the National Railroad Retirement Investment Trust and the Retirement System for Tennessee Valley Authority, are allowed to invest their money in stocks and other assets that provide higher long-term returns than Treasury bonds. The Post Office isn't.

The bottom line: More than a million workers have some kind of Post Office pension. Who's going to pay them that money, and where it's going to come from, will ultimately determine the fiscal viability of the Post Office as a business.