A respiratory virus is spreading in China. Here's why it's not the new COVID-19.

VCG/VCG via Getty Images

- Human metapneumovirus is spreading in China, but health experts say it's not a repeat of COVID-19.

- Unlike COVID-19, HMPV has been around for decades, so we know how it spreads and how to treat it.

- But China must still monitor the situation to keep it under control.

Five years after COVID-19 began spreading in the Chinese city of Wuhan, cases of human metapneumovirus, which also causes respiratory infections, have risen in the country, particularly among children.

Between December 23 and 29, cases of HMPV rose from the week before, particularly in northern China and in children under 14, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention said on Thursday. Cases of influenza, rhinovirus, and mycoplasma pneumoniae also increased, it said.

Online videos of crowded hospitals in China are reminiscent of the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Google searches in the US related to HMPV and the likelihood of a coming pandemic and lockdowns have spiked in recent days.

But HMPV doesn't pose a similar threat to COVID-19 because it's not a new virus, meaning we understand how it affects humans and most people already have some immunity against it.

HMPV causes coldlike symptoms that don't typically require treatment

HMPV usually causes coldlike symptoms, such as coughing, wheezing, a runny nose, and a sore throat, that clear on their own in three to six days. But it can lead to more serious conditions, such as bronchitis or pneumonia, particularly in young children, adults over 65, and people who are immunocompromised. Infections are most common in colder seasons.

Most people get HMPV before they turn 5, so symptoms tend to be more severe in children as they haven't yet built up immunity against it. A person gains some immunity to the virus when they first catch it, so symptoms are typically mild if they're reinfected.

It spreads through coughing and sneezing, direct contact with an infected person, or touching surfaces contaminated with the virus, such as phones.

There are no antiviral medications for HMPV, but if a patient becomes seriously ill, doctors may use oxygen therapy to help them breathe or antibiotics to treat secondary infections. There isn't a vaccine, but there are some in development.

Unlike COVID-19, HMPV is not a new virus

HMPV was first identified in the Netherlands in 2001 but is believed to have been infecting humans for decades.

"This is very different to the COVID-19 pandemic," Jill Carr, a virologist at the College of Medicine and Public Health at Flinders University in Australia, said.

"The virus was completely new in humans and arose from a spillover from animals and spread to pandemic levels because there was no prior exposure or protective immunity in the community," Carr said of COVID-19.

There's a broad understanding of how HMPV spreads and affects humans, as well as diagnostic tests to identify it.

"HMPV can certainly make people very sick, and high case numbers are a threat to effective hospital services, but the current situation in China with high HMPV cases is very different to the threats initially posed by SARS-CoV-2 resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic," Carr said.

The World Health Organization does not view HMPV in China as an emergency

A spokesperson for the World Health Organization told Business Insider via email that higher levels of respiratory illnesses, including HMPV, are expected at this time of year, adding that the rate of "influenza activity" was lower than in the same period last year.

On Thursday, the Chinese CDC advised people to take health precautions, such as maintaining good hygiene, covering their mouths and noses with a tissue or elbow when coughing or sneezing, washing their hands frequently with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, and wearing masks in crowded spaces.

But in a press conference on Friday, the Chinese government appeared to push back against online speculation that the situation could overwhelm hospitals and lead to a new pandemic, The Guardian reported.

"Respiratory infections tend to peak during the winter season," Mao Ning, a spokesperson for China's foreign ministry, said Friday. "The diseases appear to be less severe and spread with a smaller scale compared to the previous year."

China needs to share its data on the virus to lower the risk of a public health crisis

Vasso Apostolopoulos, a professor of immunology at the School of Health and Biomedical Sciences at RMIT University in Australia, said that the growing number of cases and pressure on healthcare systems in densely populated areas like China highlighted the need for enhanced surveillance strategies.

"Ensuring effective monitoring and timely responses will be key to mitigating the public health risks of this outbreak," she said.

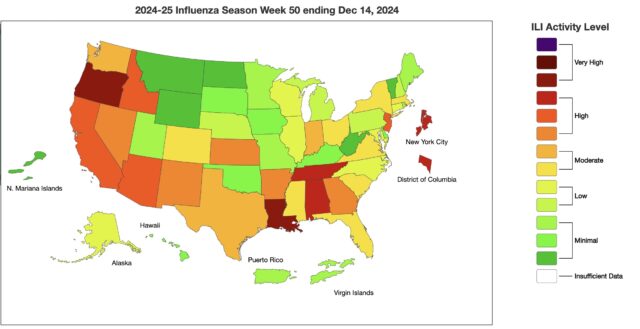

Map of ILI activity by state

Credit:

Map of ILI activity by state

Credit: