Trump touts tariffs while the market fears a recession

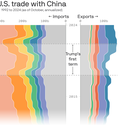

Donald Trump famously believes that "trade wars are good, and easy to win," as he tweeted in 2018. The market, however, believes the opposite: That a trade war is bad, is easy to lose, and could plunge the U.S. into an avoidable recession.

Why it matters: Trump 1.0 listened to the market. Trump 2.0 is very different.

- Traders are no longer convinced they can rely on the "Trump put," the idea that the president will reverse course on policies the market doesn't like.

What they're saying: The clearest articulation of the Trump administration's attitude to the market came from Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent.

- "Wall Street's done great," he said Tuesday, "but we have a focus on small business and the consumers. So we are going to rebalance the economy."

Between the lines: Bessent singled out "the level of the 10-year bond" as "one of the biggest wins for the American people."

- A former macro hedge fund manager, Bessent knows the decline in long-term interest rates is a function of pessimism about future growth, and expectations that the Fed is going to have to keep rates low to stimulate employment.

By the numbers: On February 11, the market put just a 1% probability on the Fed cutting rates four times this year, assuming each cut is 25 basis points.

- Today, the probability of at least four cuts has risen to 30%. The probability of three or more rate cuts has ballooned to 62%.

- Given the stubbornness of inflation, which is likely to become even more stubborn as higher tariffs start to bite, the only reason for the Fed to cut that many times would be a significant economic slowdown, or perhaps even a recession.

The big picture: There is "a new reality of higher domestic prices and weaker growth, owing to Trump's tariff measures," George Vessey, the lead macro strategist at Convera, wrote in a note.

- That in turn is causing the dollar to weaken, which is the opposite of what should happen when tariffs rise, according to textbook economics.

- It's true that all things equal, U.S. tariffs should cause the dollar to strengthen, as fewer dollars get sold to pay for imports.

- But these tariffs are so big, and so potentially damaging to the U.S. economy, that — according to foreign exchange markets — domestic macroeconomic effects are likely to dwarf the effects of capital flows.

Zoom out: The dollar has historically benefited from "safe haven" status. It's a reliable store of value during volatile times.

- When the president of the United States is the person causing all the volatility, however, the dollar looks less attractive on that front.

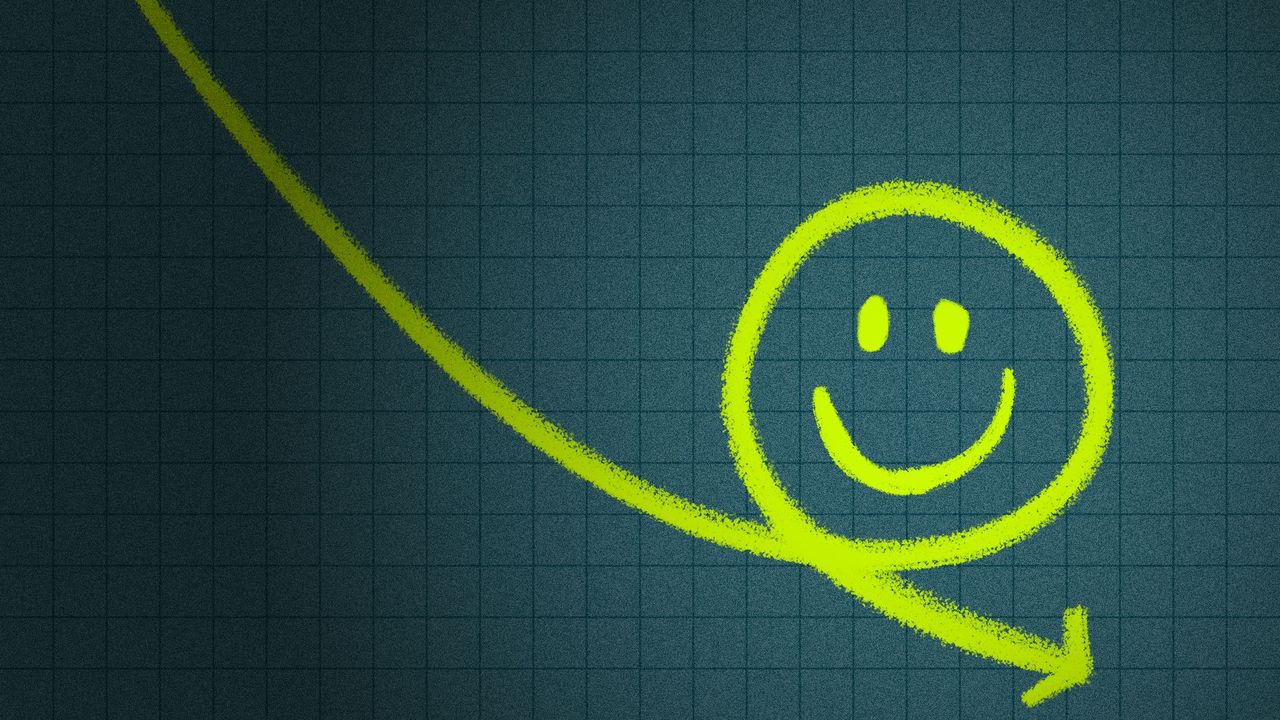

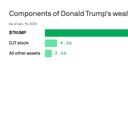

The bottom line: The stock market is not the economy, especially when it's dominated by megacap tech companies.

- But there are many other indicators of where the markets think the economy is headed, and all of them are flashing "very worried."