Copyright Abuse Is Getting Luigi Mangione Merch Removed From the Internet

An entity claiming to be United Healthcare is sending bogus copyright claims to internet platforms to get Luigi Mangione fan art taken off the internet, according to the print-on-demand merch retailer TeePublic. An independent journalist was hit with a copyright takedown demand over an image of Luigi Mangione and his family she posted on Bluesky, and other DMCA takedown requests posted to an open database and viewed by 404 Media show copyright claims trying to get “Deny, Defend, Depose” and Luigi Mangione-related merch taken off the internet, though it is unclear who is filing them.

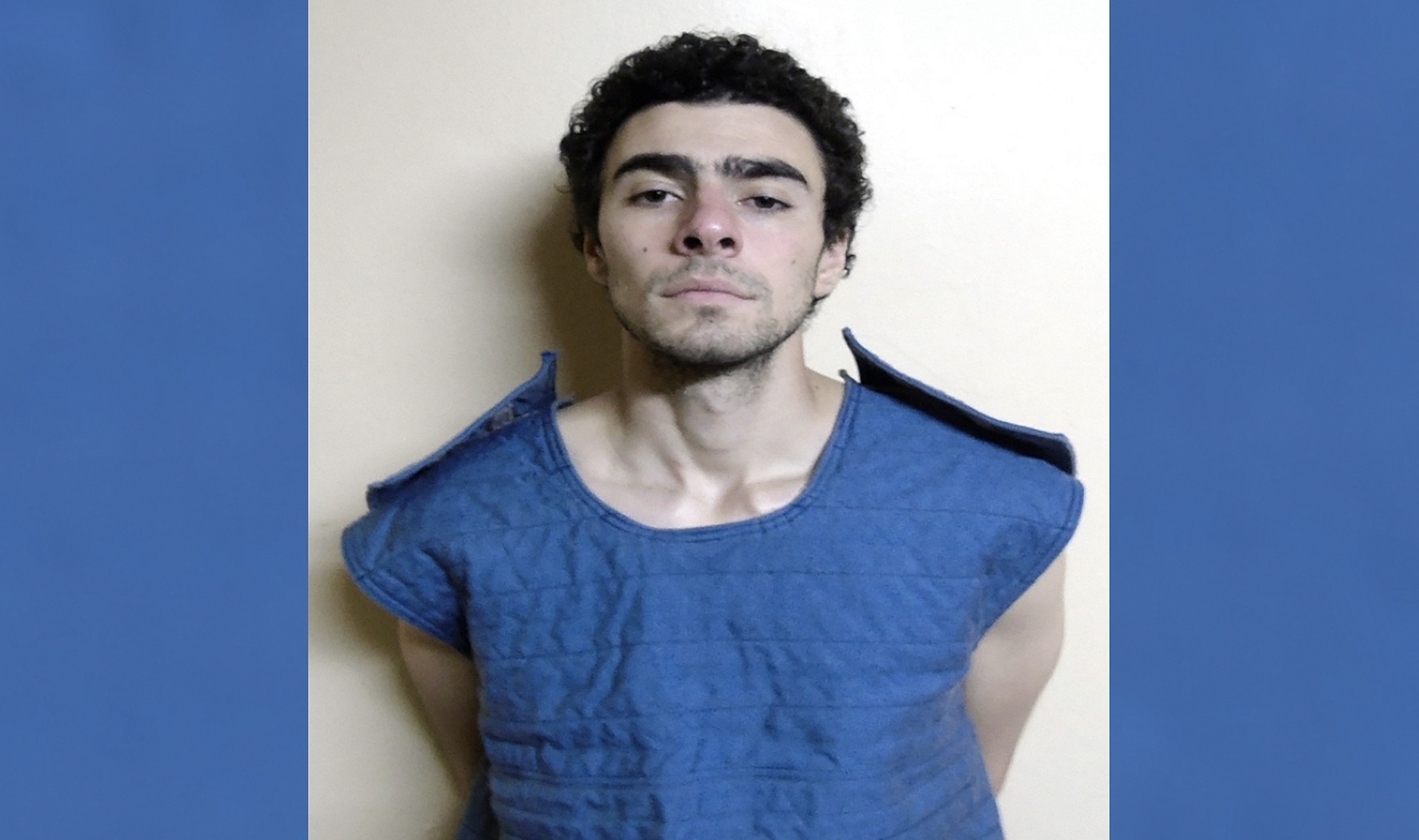

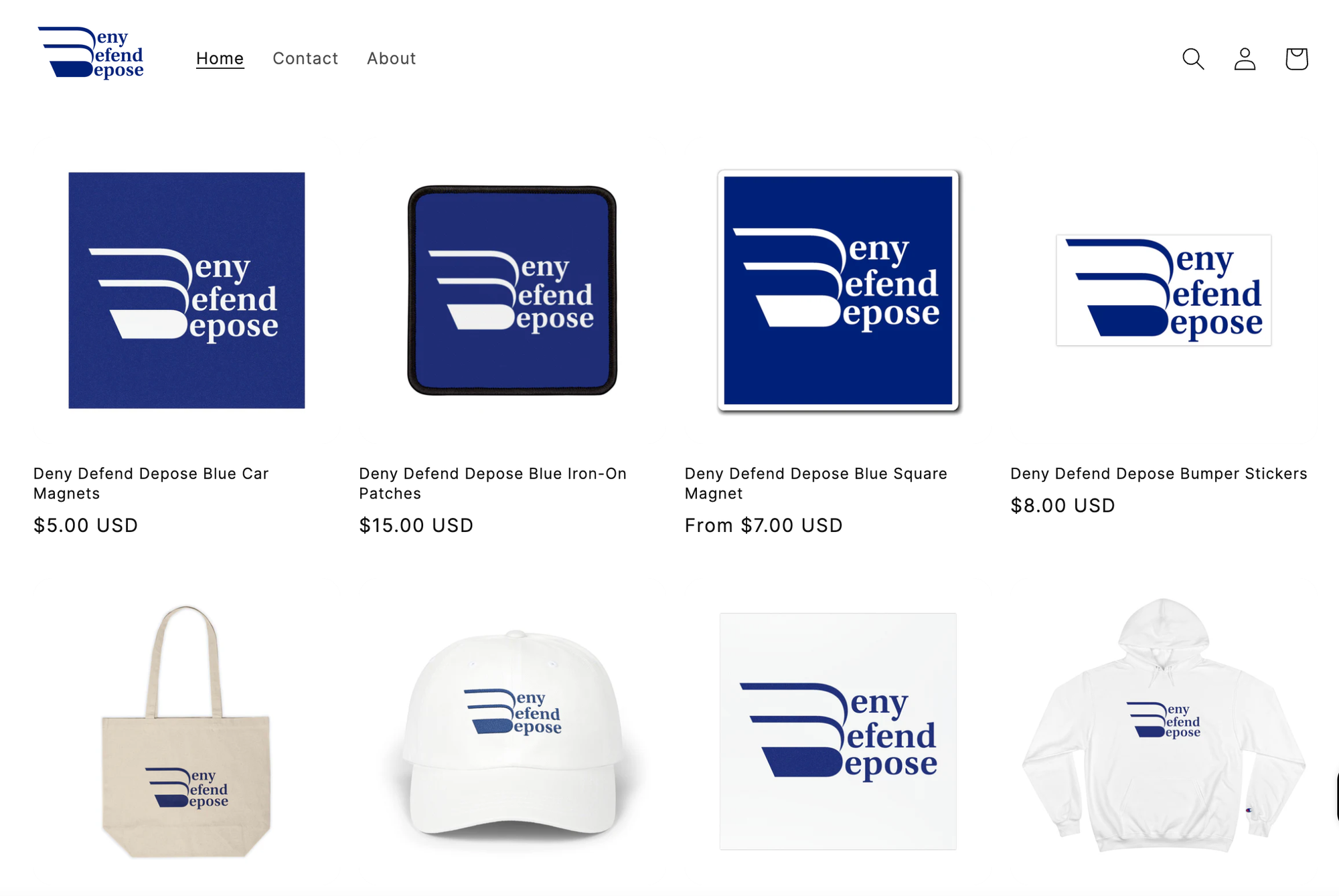

Artist Rachel Kenaston was selling merch with the following design on TeePublic, a print-on-demand shop:

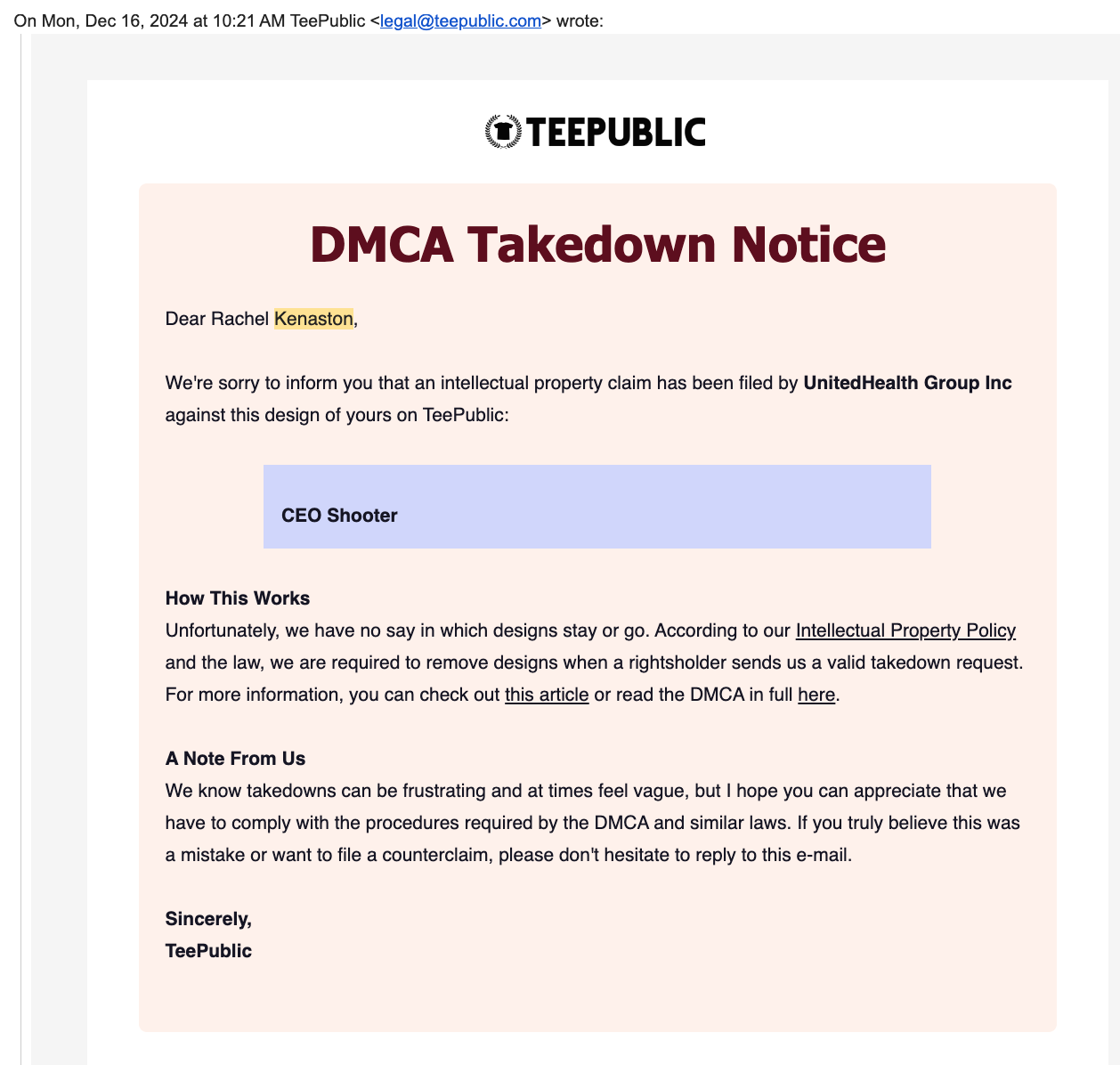

She got an email from TeePublic that said “We're sorry to inform you that an intellectual property claim has been filed by UnitedHealth Group Inc against this design of yours on TeePublic,” and said “Unfortunately, we have no say in which designs stay or go” because of the DMCA. This is not true—platforms are able to assess the validity of any DMCA claim and can decide whether to take the supposedly infringing content down or not. But most platforms choose the path of least resistance and take down content that is obviously not infringing; Kenaston’s clearly violates no one’s copyright. Kenaston appealed the decision and TeePublic told her: “Unfortunately, this was a valid takedown notice sent to us by the proper rightsholder, so we are not allowed to dispute it,” which, again, is not true.

The threat was framed as a “DMCA Takedown Request.” The DMCA is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, an incredibly important copyright law that governs most copyright law on the internet. Copyright law is complicated, but, basically, DMCA takedowns are filed to give notice to a social media platform, search engine, or website owner to inform them that something they are hosting or pointing to is copyrighted, and then, all too often, the social media platform will take the content down without much of a review in hopes of avoiding being being sued.

“It's not unusual for large companies to troll print-on-demand sites and shut down designs in an effort to scare/intimidate artists, it's happened to me before and it works!,” Kenaston told 404 Media in an email. “The same thing seems to be happening with UnitedHealth - there's no way they own the rights to the security footage of Luigi smiling (and if they do.... wtf.... seems like the public should know that) but since they made a complaint my design has been removed from the site and even if we went to court and I won I'm unsure whether TeePublic would ever put the design back up. So basically, if UnitedHealth's goal is to eliminate Luigi merch from print-on-demand sites, this is an effective strategy that's clearly working for them.”

There is no world in which the copyright of a watercolor painting of Luigi Mangione surveillance footage done by Kenaston is owned by United Health Group as it quite literally has nothing to do with anything that the company owns. It is illegal to file a DMCA unless you have a “good faith” belief that you are the rights holder (or are representing the rights holder) of the material in question.

“What is the circumstance under which United Healthcare might come to own the copyright to a watercolor painting of the guy who assassinated their CEO?” tech rights expert and science fiction author Cory Doctorow told 404 Media in a phone call. “It’s just like, it’s hard to imagine” a lawyer thinking that, he added, saying that it’s an example of “copyfraud.”

United Healthcare did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and TeePublic also did not respond to a request for comment. It is theoretically possible that another entity impersonated United Healthcare to request the removal because copyfraud in general is so common.

But Kenaston’s work is not the only United Healthcare or Luigi Mangione-themed artwork on the internet that has been hit with bogus DMCA takedowns in recent days. Several platforms publish the DMCA takedown requests they get on the Lumen Database, which is a repository of DMCA takedowns.

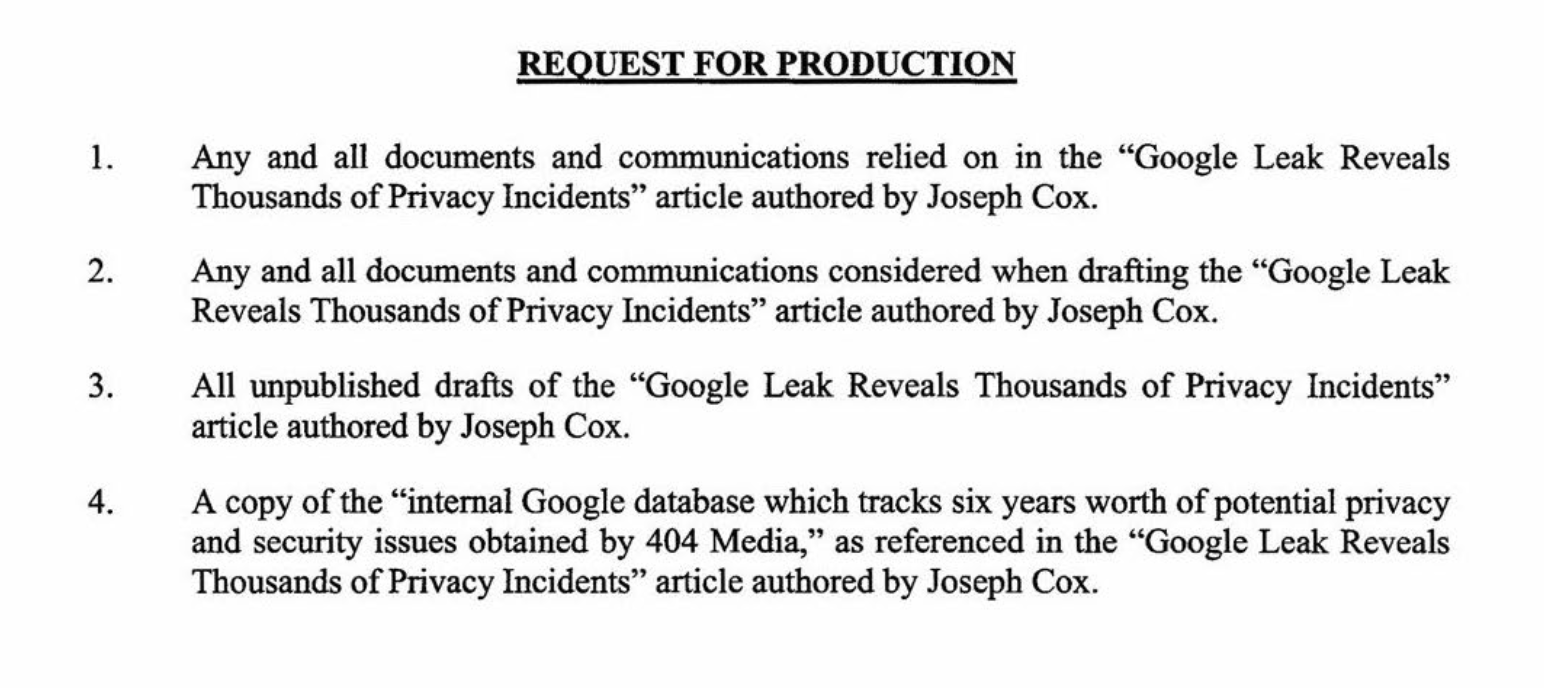

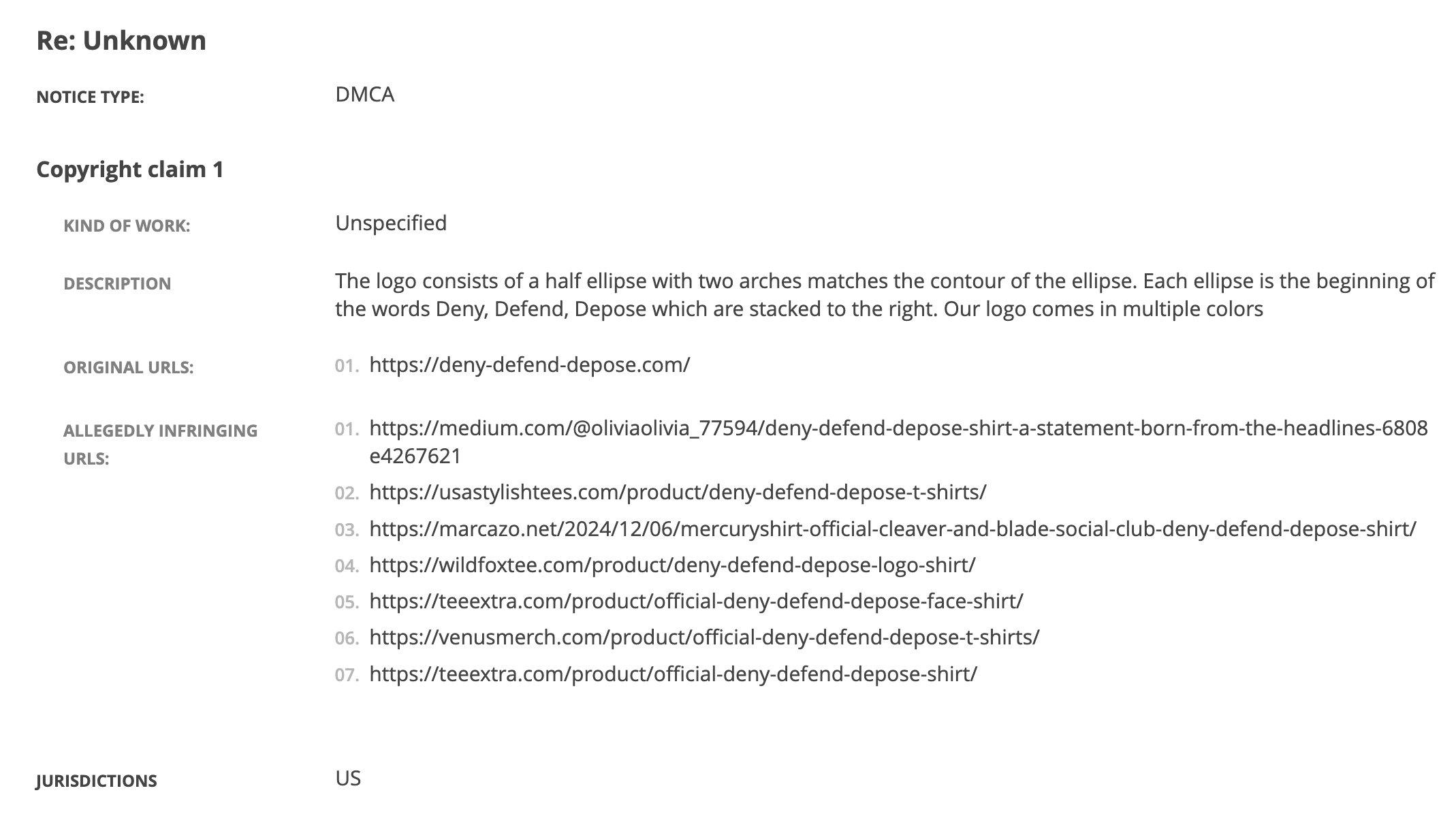

On December 7, someone named Samantha Montoya filed a DMCA takedown with Google that targeted eight websites selling “Deny, Defend, Depose” merch that uses elements of the United Healthcare logo. Montoya’s DMCA is very sparse, according to the copy posted on Lumen: “The logo consists of a half ellipse with two arches matches the contour of the ellipse. Each ellipse is the beginning of the words Deny, Defend, Depose which are stacked to the right. Our logo comes in multiple colors.”

Medium, one of the targeted websites, has deleted the page that the merch was hosted on. It is not clear from the DMCA whether the person filing this is associated with United Healthcare, or whether they are associated with deny-defend-depose.com and are filing against copycats. Deny-defend-depose.com did not respond to a request for comment. Similarly, a DMCA takedown filed by someone named Manh Nguyen targets a handful of “Deny, Defend, Depose” and Luigi Mangione-themed t-shirts on a website called Printiment.com.

Based on the information on Lumen Database, there is unfortunately no way to figure out who Samantha Montoya or Manh Nguyen are associated with or working on behalf of.

Not Just Fan Art

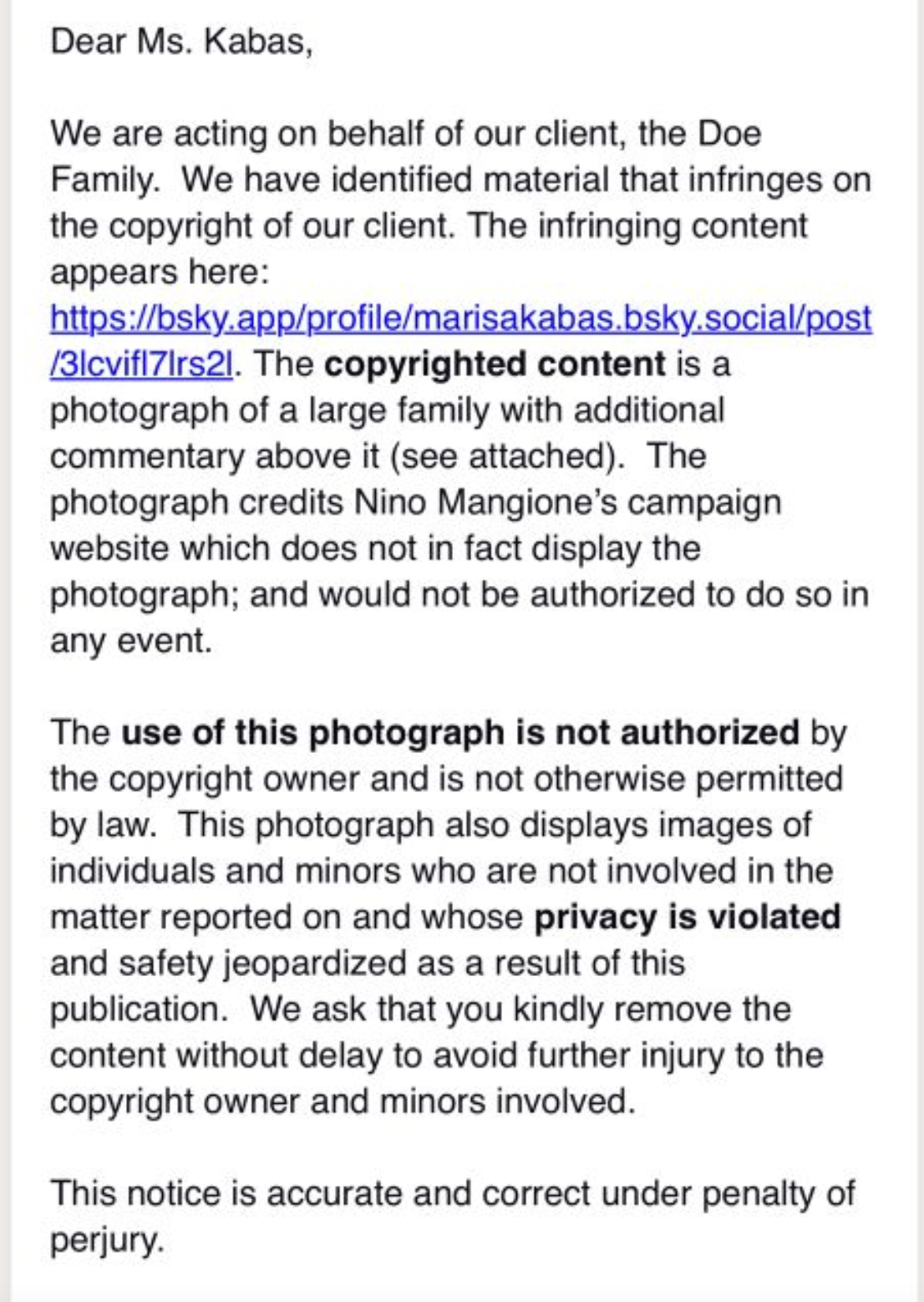

Over the weekend, a lawyer demanded that independent journalist Marisa Kabas take down an image of Luigi Mangione and his family that she posted to Bluesky, which was originally posted on the campaign website of Maryland assemblymember Nino Mangione.

The lawyer, Desiree Moore, said she was “acting on behalf of our client, the Doe Family,” and claimed that “the use of this photograph is not authorized by the copyright owner and is not otherwise permitted by law.”

Moore said that Nino Mangione’s website “does not in fact display the photograph,” even though the Wayback Machine shows that it obviously did display the image. In a follow-up email to Kabas, Moore said “the owner of the photograph has not authorized anyone to publish, disseminate, or otherwise use the photograph for any purpose, and the photograph has been removed from various digital platforms as a result,” which suggests that other websites have also been threatened with takedown requests. Moore also said that her “client seeks to remain anonymous” and that “the photograph is hardly newsworthy.” The New York Post also published the image, and blurred versions of the image remain on its website. The New York Post did not respond to a request for comment. Kabas deleted her Bluesky post “to avoid any further threats,” she said.

“It feels like a harbinger of things to come, coming directly after journalists for something as small as a social media post,” Kabas, who runs the excellent independent site The Handbasket, told 404 Media in a video chat. “They might be coming after small, independent publishers because they know we don’t have the money for a large legal defense, and they’re gonna make an example out of us, and they’re going to say that if you try anything funny, we’re going to try to bankrupt you through a frivolous lawsuit.”

The takedown request to Kabas in particular is notable for a few reasons. First, it shows that the Mangione family or someone associated with it is using the prospect of a copyright lawsuit to threaten journalists for reporting on one of the most important stories of the year, which is particularly concerning in an atmosphere where journalists are increasingly being targeted by politicians and the powerful. But it’s also notable that the threat was sent directly to Kabas for something she posted on Bluesky, rather than being sent to Bluesky itself. (Bluesky did not respond to a request for comment for this story, and we don’t know if Bluesky also received a takedown request about Kabas’s post.)

Sometimes for better, but mostly for worse, social media platforms have long served as a layer between their users and copyright holders (and their lawyers). YouTube deals with huge numbers of takedown requests filed under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. But to avoid DMCA headaches, it has also set up automated tools such as ContentID and other algorithmic copyright checks that allow copyright holders to essentially claim ownership of—and monetization rights to—supposedly copyrighted material that users upload without invoking the DMCA. YouTube and other social media platforms have also infamously set up “copy strike” systems, where people can have their channels demonetized, downranked in the algorithm, or deleted outright if rights holders claim a post or video violates their copyright or if an automated algorithm does.

This layer between copyright holders and social media users has created all kinds of bad situations where social media platforms overzealously enforce against content that may be OK to use under fair use provisions or where someone who does not own the copyright at all abuses the system to get content they don’t like taken down, which is what happened to Kenaston.

Copyright takedown processes under social media companies almost always err on the side of copyright holders, which is a problem. On the other hand, because social media companies are usually the ones receiving DMCAs or otherwise dealing with copyright, individual social media users do not usually have to deal directly with lawyers who are threatening them for something they tweeted, uploaded to YouTube, or posted on Bluesky.

There is a long history of powerful people and companies abusing copyright law to get reporting or posts they don’t like taken off the internet. But very often, these attempts backfire as the rightsholder ends up Streisand Effecting themselves. But in recent weeks, independent journalists have been getting these DMCA takedown requests—which are explicit legal threats—directly. A “reputation management company” tried to bribe Molly White, who runs Web3IsGoingGreat and Citation Needed, to delete a tweet and a post about the arrest of Roman Ziemian, the cofounder of FutureNet, for an alleged crypto fraud. When the bribe didn’t work because White is a good journalist who doesn’t take bribes, she was hit with a frivolous DMCA claim, which she wrote about here.

These sorts of threats do happen from time to time, but the fact that several notable ones have happened in quick succession before Trump takes office is notable considering that Trump himself said earlier this week that he feels emboldened by the fact that ABC settled a libel lawsuit with him after agreeing to pay him a total of $16 million. That case—in which George Stephanopoulos said that Trump was found civilly liable of “rape” rather than of “sexual assault”—has scared the shit out of media companies.

This is because libel cases for public figures consider whether that person’s reputation was actually harmed, whether the news outlet acted with “actual malice,” rather than just negligence, and the severity of the harm inflicted. Considering Trump is the most public of public figures, that he still won the presidency, and that a jury did find him liable for a “sexual assault,” this is a terrible kowtowing to power that sets a horrible precedent.

Trump’s case with ABC isn’t exactly related to a DMCA takedown filed over a Bluesky post, but they’re both happening in an atmosphere in which powerful people feel empowered to target journalists.

“There’s also the Kash Patel of it all. They’re very openly talking about coming after journalists. It’s not hypothetical,” Kabas said, referring to Trump’s pick to lead the FBI. “I think that because the new administration hasn’t started yet, we don’t know for sure what that’s going to look like,” she said. “But we’re starting to get a taste of what it might be like.”

What’s happening to Kabas and Kenaston highlights how screwed up the internet is, and how rampant DMCA abuse is. Transparency databases like Lumen help a lot, but it’s still possible to obscure where any given takedown request is coming from, and platforms like TeePublic do not post full DMCAs.