DeepSeek-V3 shows China's AI getting better — and cheaper

Chinese AI makers have learned to build powerful AI models that perform just short of the U.S.'s most advanced competition while using far less money, chips and power.

Why it matters: American policies restricting the flow of top-end AI semiconductors and know-how to China may have helped maintain a short U.S. lead at the outer reaches of the AI performance curve — but they've also accelerated Chinese progress in building high-end AI more efficiently.

Catch up quick: In late December, Hangzhou-based DeepSeek released V3, an open-source large language model whose performance on various benchmark tests puts it in the same league as OpenAI's 4o and Anthropic's Claude 3.5 Sonnet.

- Those are the most advanced AI models these companies currently offer to the broad public, though both OpenAI and Anthropic have next-generation models in their pipeline.

Stunning stat: Training V3 cost DeepSeek roughly $5.6 million, according to the company.

- OpenAI, Google and Anthropic have reportedly spent hundreds of millions of dollars to build and train their current models, and expect to spend billions in the future.

- AI pioneer Andrej Karpathy called DeepSeek's investment "a joke of a budget" and described the result as "a highly impressive display of research and engineering under resource constraints."

Between the lines: In an interview last year, DeepSeek CEO Liang Wenfeng said, "Money has never been the problem for us; bans on shipments of advanced chips are the problem."

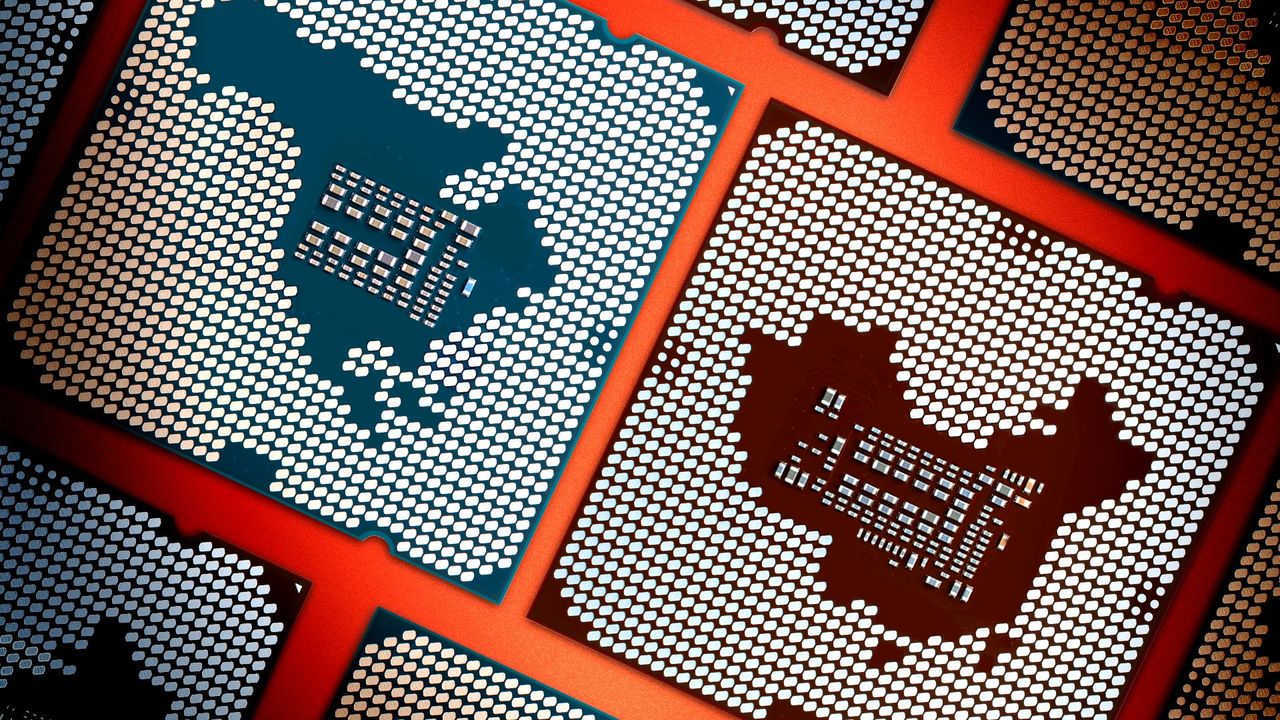

- The V3 model was trained on Nvidia H800 chips, a less-powerful version of a chip the U.S. banned for export to China in 2022. Export of the H800 was then prohibited when the U.S. tightened controls again the following year.

The big picture: Some U.S. officials have argued for restricting China's access to advanced AI chips even further in hopes of slowing the country's development of the technology.

- On Monday, the Biden administration announced another big round of export controls aimed at choking the supply of chips to China via third-party countries.

What's next: Advances like V3 and OpenAI's powerful new "reasoning" model, o3, have lent weight to recent claims by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and other industry leaders who predict the industry is closing in fast on artificial general intelligence (AGI). (Plenty of other observers remain skeptical.)

- AGI — or AI that can solve problems and perform tasks at a human or beyond-human level — is a holy grail for AI researchers, and many in the industry and U.S. government believe the technology's first developer will win a massive economic, scientific and security edge.

- Biden's latest export controls have led some observers to conclude the government shares the growing sense that AGI is close.

- "This is a 'break in case of emergency' policy, and the Biden administration identified that the emergency is that AGI is just a few years away," Gregory Allen, director of the Wadhwani AI Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, tells Axios.

Yes, but: AGI is also not well-defined, and both optimists and pessimists have complained that it's become a moving goalpost.

/2024/12/11/1733957733138.gif)

/2024/12/11/1733957733138.gif)