From Helena to the Hague, climate court cases pile up

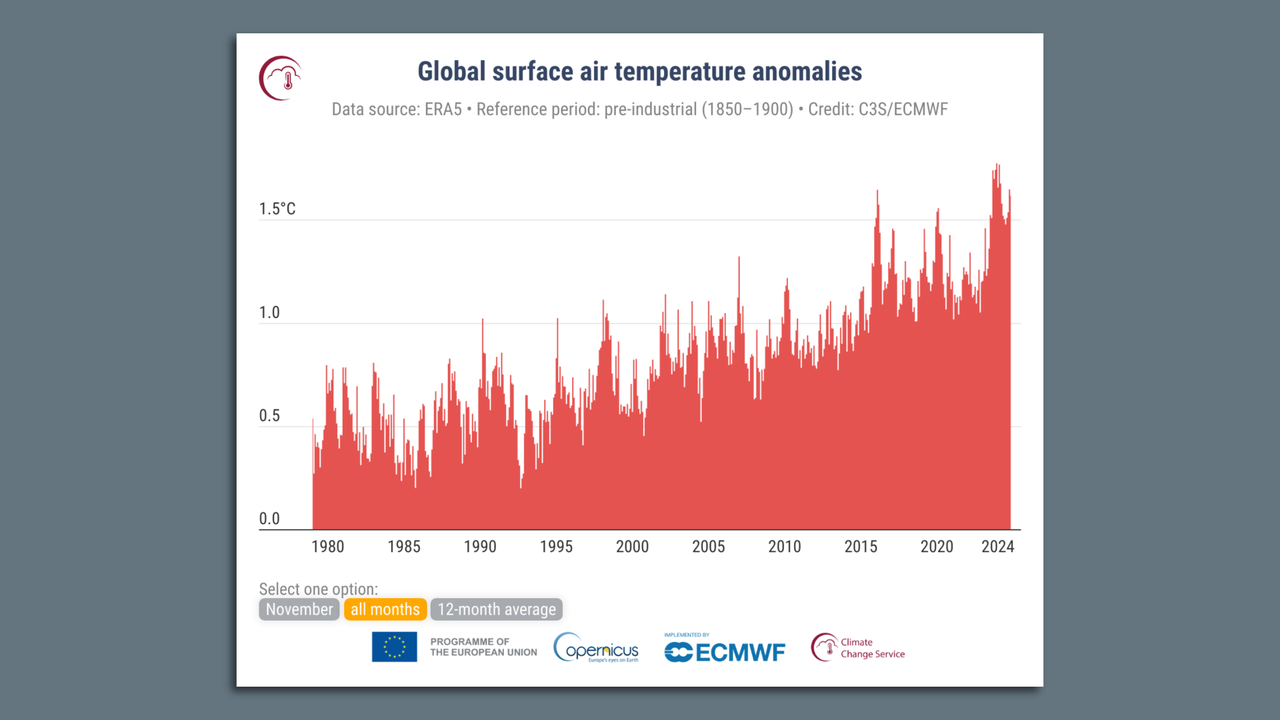

Court cases involving climate change are taking on increased importance with global efforts proceeding far slower than the climate is warming and national policy subject to whiplash.

Why it matters: Cases under deliberation at the Hague, newly decided in Montana and in process elsewhere show that courts are increasingly receptive to the duty of governments and corporations to limit emissions.

What they're saying: The surge in cases is a symptom of those entities' failures to act on climate, says Patrick Parenteau of the Vermont Law School.

- "The courts aren't going to save us, but when the political process is failing, that's where you turn to," he told Axios in an interview.

- Questions remain about the practical implications of court rulings, and whether they can truly cut planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions, are more symbolic measures — or lie somewhere in between.

The big picture: In the U.S., cities, states and citizens have pursued legal action to force the government and fossil fuel industry to take responsibility for causing global warming and enact new emissions curbs or provide compensation for climate change-related damage.

- Many of these lawsuits have been quashed on jurisdictional grounds or for other reasons.

- This month, though, has brought two major developments that may mark a turning point in climate change-related legal battles.

- At the International Court of Justice at the Hague, the tiny island nation of Vanuatu brought a case seeking an advisory opinion on the obligations that countries have to combat global warming.

- A rare two weeks of public testimony has concluded, but not before fractures between industrialized and developing nations were laid bare.

The intrigue: The U.S. and Russia, among other nations, argued that human rights law shouldn't apply.

- They want any advisory opinion to stick to obligations under climate pacts like the Paris Agreement, while developing nations argued that major polluters are violating more vulnerable nations' basic human rights.

Then, on Wednesday, a 6-1 majority on the Montana Supreme Court backed a lower court's decision that the state's fossil fuel policies and lack of action to curb global warming violated young people's constitutional right to a clean environment.

- The decision in Held v. Montana also directs state agencies to consider greenhouse gas emissions from proposed development projects.

- Montana is a significant producer of coal, the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel. It's also an increasingly important state for mining minerals used in renewable energy sources.

State of play: The Montana decision is especially significant since several other states have similar constitutional provisions, potentially leading to a domino effect of state legal actions to force certain steps to be taken.

- Illinois, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts and Rhode Island have similar constitutional provisions, and efforts are underway to enact language in other states, said Michael Gerrard, a climate change law scholar at Columbia University.

- In Hawaii, a case with similarities to Montana's was settled on favorable terms to the plaintiffs, he noted. The state committed to decarbonizing its transportation system, among other steps.

Zoom out: Gerrard said legal action on climate change can be effective in settings in which courts are independent and influential.

- "We're certainly seeing a tremendous growth of climate litigation," he told Axios in an interview.

- He noted cases in the Netherlands that spurred governmental action and a Supreme Court ruling in Nepal that resulted in Parliament passing a climate law.

- "The courts are having an influence in some cases," Gerrard said.

Yes, but: Some court victories for climate activists have turned into setbacks on appeal, however.

- A 2021 ruling by a Dutch district court directing the oil and gas giant Shell to cut its emissions by 45% by 2030 relative to 2019 levels was overturned in November.

- Between the 2021 decision and the appeals court's actions this year, Shell made more investments in its oil and gas production while deemphasizing its renewables business, in an effort to benefit investors.

- The company also moved its headquarters out of the Netherlands, though that was for multiple reasons including tax considerations.

Between the lines: This raises the question of whether such cases make a meaningful difference for what really matters: greenhouse gas emissions.

- In the Shell case, that answer is clearly no.

- And even in the Montana case — which many activists hailed as a breakthrough decision — the only relief the state Supreme Court granted was to ensure that planet-warming emissions would be incorporated into project planning.

The bottom line: Neither the political process, nor the courts, are successfully limiting climate change and its many damaging effects.