Got Sniffly Allergies? Your Funky Nose Fungi Might Be to Blame

People with allergies or asthma have more diverse fungal communities thriving in their noses, according to new research.

BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Creating "mirror life" could be one of science's greatest breakthroughs, but some researchers who began the effort are now calling for it to stop.

No mirror-life microorganisms exist yet. However, 38 scientists warned in a paper published in the journal Science on December 12 that if someone created one and it escaped the lab, it could cause a catastrophic multi-species pandemic.

"We're basically giving instructions of how to make a perfect bioweapon," Kate Adamala, a co-author of the paper and a chemist who leads a synthetic biology lab at the University of Minnesota, told Business Insider.

As the risks became clear, Adamala ended her lab's efforts toward building a mirror cell. Her multi-year grant for that facet of their research expired and she decided not to apply for renewal, she said.

Now she's urging other scientists to do the same, along with the 37 other researchers.

"Although we were initially skeptical that mirror bacteria could pose major risks, we have become deeply concerned," they wrote in the paper.

Mirror biology takes a fundamental rule of life on Earth, called chirality, and flips it.

Chirality is the simple fact that molecules — like sugars and amino acids — point in one of two directions. They are either right-handed or left-handed.

For some reason, though, life will only use one chiral form of each molecule. DNA, for example, only uses right-handed sugars for its backbone. That's why it twists to the right.

In mirror biology, scientists aim to create living cells where all the chirality is flipped. Where natural life uses a right-handed peptide, to build proteins, mirror life would use the same peptide in its left-handed form.

Adamala's research was focused on making mirror peptides, which can help create longer-lasting pharmaceuticals.

A full mirror cell was the long-term goal of that research. Mirror cells could help prevent contamination in bioreactors that use bacteria for green chemical manufacturing because, in theory, they wouldn't interact with natural microorganisms.

"You could have this perfect bioreactor that can just sit there and you can stick your finger into it and you're not going to contaminate it," Adamala said. "That's also precisely the problem."

A mirror bacteria could bypass the natural checks and balances of life, like competing with other bacteria or battling our immune systems.

Adamala said "the death sentence" for her mirror-cell research came when she spoke to immunologists. They explained that for humans, other animals, and plants, immune system activation depends on chirality.

Immune cells recognize pathogens' proteins, but they wouldn't detect the inverse versions of those proteins that mirror cells would use.

A mirror pathogen "doesn't interact with the host. It just uses it as a warm incubator with a lot of nutrients," Adamala said.

If a mirror bacteria escaped the lab, it could cause slow, persistent infections that can't be treated with antibiotics (because those, too, rely on chirality).

Because they wouldn't face any immune resistance, mirror bacteria wouldn't need to specialize in infecting corn, or goats, or birds.

"It would be a disease of anything that lives that can be infected," Adamala said.

In the worst-case scenario, a mirror bacteria would multiply endlessly, unfettered. It would take over its hosts and eventually kill them. It would destroy crops. It would have no predators. It would overwhelm entire ecosystems, swapping out portions of our natural world for a new mirror world.

Ting Zhu, one of the leading researchers trying to make a mirror cell, told BI in an email that he supports being cautious but doesn't think "a complete mirror-image bacterium can be synthesized in the foreseeable future."

Zhu leads a mirror-image biology lab at Westlake University in China. He was not involved in the Science paper.

Adamala estimates that the world's first mirror bacteria is still about a decade away. She argues that's exactly why the research should stop now before it builds all the tools that someone could use to make that final leap.

"No one can do it on their own right now," Adamala said. "The technology is not mature enough, which means we're pretty well safeguarded against someone crazy enough to say, 'I'll just go do it.'"

In the meantime, Adamala and the other paper authors invited more research and scrutiny on the risks they've identified.

"If someone does prove us wrong, that would make me really happy," she said.

We think of squirrels as adorably harmless creatures, admiring their bushy tails and twitchy little noses and the way they cram their cheeks with nuts or seeds to bring back to their nests for later. But the rodents turn out to be a bit more bloodthirsty than we thought. According to a new paper published in the Journal of Ethology, California ground squirrels have been caught in the act—many times over—of chasing, killing, and eating voles.

Co-author Jennifer Smith, a biologist at the University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire, described the behavior as "shocking," given the sheer number of times they watched squirrels do this. “We had never seen this behavior before," she said. "Squirrels are one of the most familiar animals to people. We see them right outside our windows; we interact with them regularly. Yet here’s this never-before-encountered-in-science behavior that sheds light on the fact that there’s so much more to learn about the natural history of the world around us.”

Squirrels mainly consume acorns, seeds, nuts, and fruits, but they have been known to supplement that diet with insects and, occasionally, by stealing eggs or young hatchlings from nests. And back in 1993, biologist J.R Callahan caused a stir by reporting that as many as 30 species of squirrel could be preying on smaller creatures: namely, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and the occasional small mammal.

© Sonja Wild/UC Davis

On Friday, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced that it would begin a nationwide testing program for the presence of the H5N1 flu virus, also known as the bird flu. Testing will focus on pre-pasteurized milk at dairy processing facilities (pasteurization inactivates the virus), but the order that's launching the program will require anybody involved with milk production before then to provide samples to the USDA on request. That includes "any entity responsible for a dairy farm, bulk milk transporter, bulk milk transfer station, or dairy processing facility."

The ultimate goal is to identify individual herds where the virus is circulating and use the agency's existing powers to do contact tracing and restrict the movement of cattle, with the ultimate goal of eliminating the virus from US herds.

At the time of publication, the CDC had identified 58 cases of humans infected by the H5N1 flu virus, over half of them in California. All but two have come about due to contact with agriculture, either cattle (35 cases) or poultry (21). The virus's genetic material has appeared in the milk supply and, although pasteurization should eliminate any intact infectious virus, raw milk is notable for not undergoing pasteurization, which has led to at least one recall when the virus made its way into raw milk. And we know the virus can spread to other species if they drink milk from infected cows.

© Credit: mikedabell

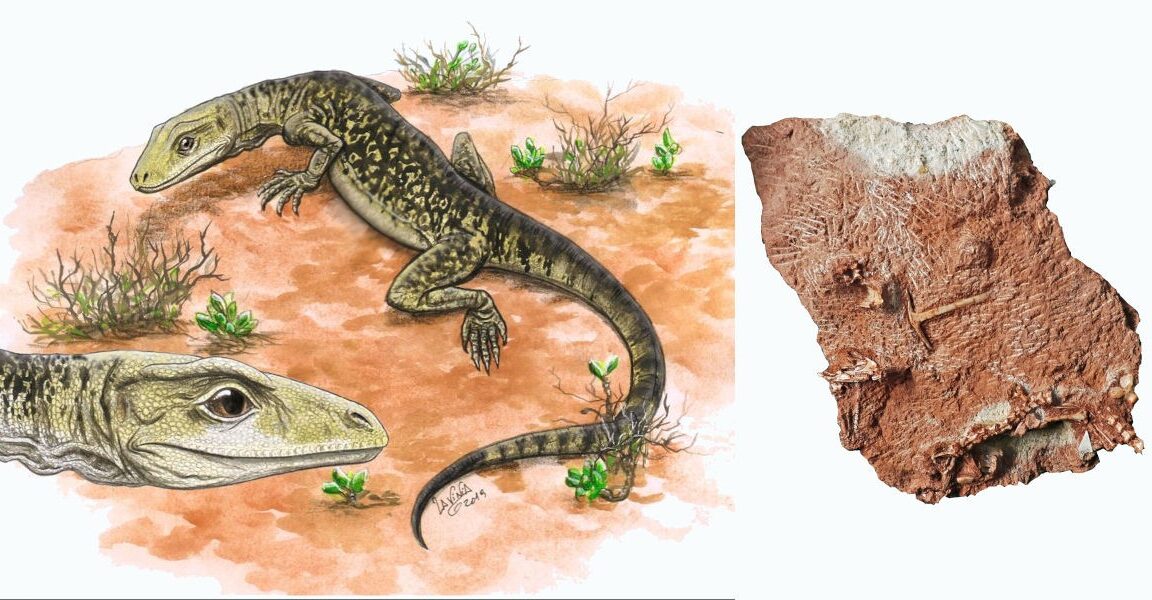

Lizards are ancient creatures. They were around before the dinosaurs and persisted long after dinosaurs went extinct. We’ve now found they are 35 million years older than we thought they were.

Cryptovaranoides microlanius was a tiny lizard that skittered around what is now southern England during the late Triassic, around 205 million years ago. It likely snapped up insects in its razor teeth (its name means “hidden lizard, small butcher”). But it wasn’t always considered a lizard. Previously, a group of researchers who studied the first fossil of the creature, or holotype, concluded that it was an archosaur, part of a group that includes the extinct dinosaurs and pterosaurs along with extant crocodilians and birds.

Now, another research team from the University of Bristol has analyzed that fossil and determined that Cryptovaranoides is not an archosaur but a lepidosaur, part of a larger order of reptiles that includes squamates, the reptile group that encompasses modern snakes and lizards. It is now also the oldest known squamate.

© Lavinia Gandolfi/David Whiteside, Sophie Chambi-Trowell, Mike Benton and the Natural History Museum, London