Inside ICE’s Supercharged Facial Recognition App of 200 Million Images

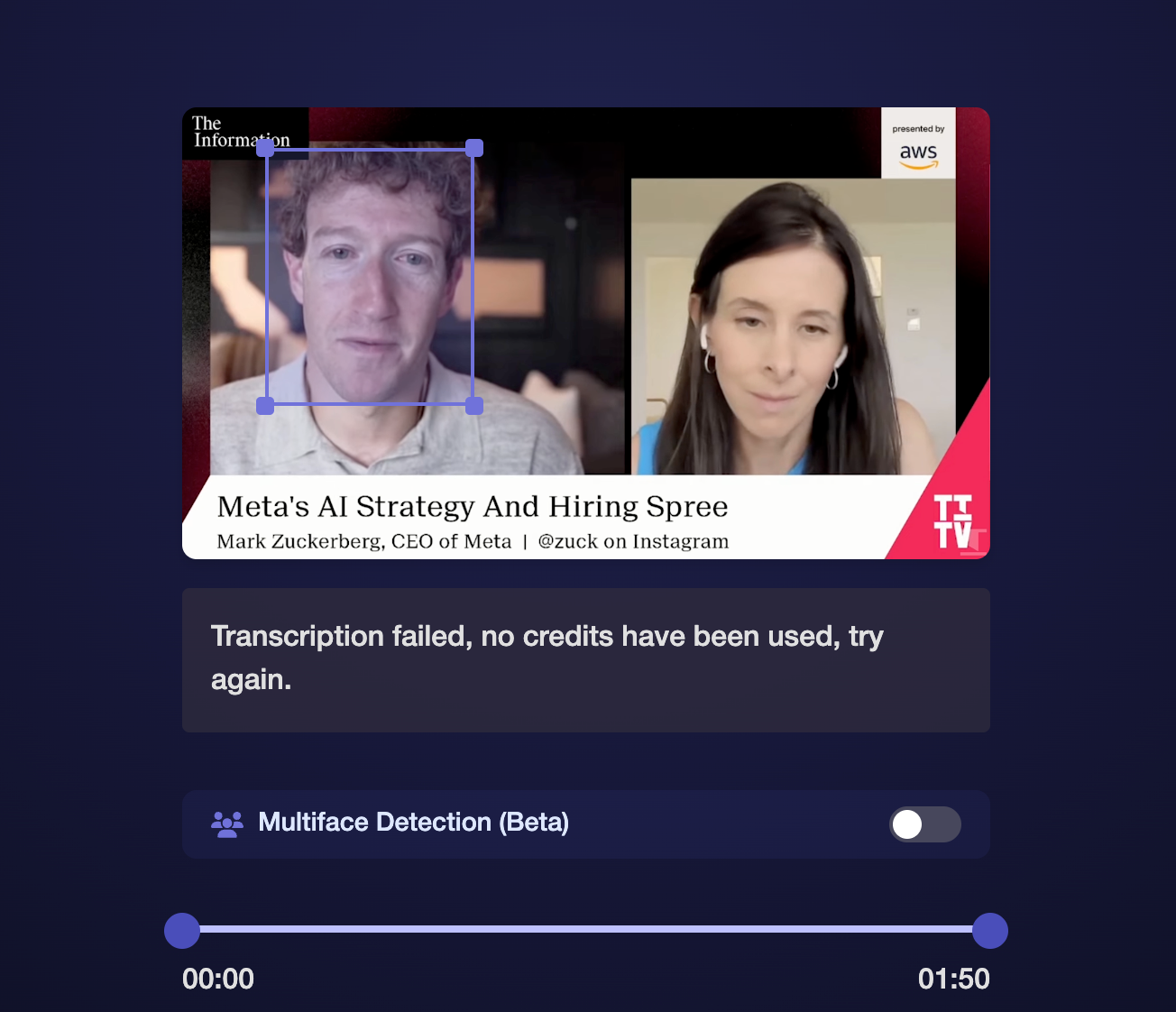

ICE officers are able to point their smartphone’s camera at a person and near instantaneously run their face against a bank of 200 million images, then pull up their name, date of birth, nationality, unique identifiers such as their “alien” number, and whether an immigration judge has determined they should be deported from the country, according to ICE material viewed by 404 Media.

The new material, which includes user manuals for ICE’s recently launched internal app called Mobile Fortify, provides granular insight into exactly how ICE’s new facial recognition app works, what data it can return on a subject, and where ICE is sourcing that data. The app represents an unprecedented linking of government databases into a single tool, including from the State Department, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the FBI, and state records. It also includes the potential for ICE to later add commercially available databases that contain even more personal data on people inside the United States.

“This app shows that biometric technology has moved well beyond just confirming someone's identity. In the hands of ICE officers, it's becoming a way to retrieve vast amounts of data about a person on demand just by pointing a camera in their face,” Dave Maass, director of investigations at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), told 404 Media. “The more they streamline its use, the more they streamline its abuse. When an officer says, ‘papers please,’ you could choose to say nothing and face the consequences; with face recognition, your options are diminished.”

A memo sent to ICE officials describes Mobile Fortify as “Biometric Capture Made Easy.” Beyond facial recognition, it has a feature that allows ICE officers to use a smartphone camera to scan and save a person’s fingerprints with a feature it called “contactless fingerprints.” It says the app “allows officers to run remote identity checks in the field by capturing contactless fingerprints and facial images using their ICE-issued iPhones. The application runs facial images against over 200 million DHS and Department of State records.”

A demonstration included in the material shows a person standing in front of a phone’s camera with an ellipse on the screen where their face will be scanned. “Searching Face,” the app says.

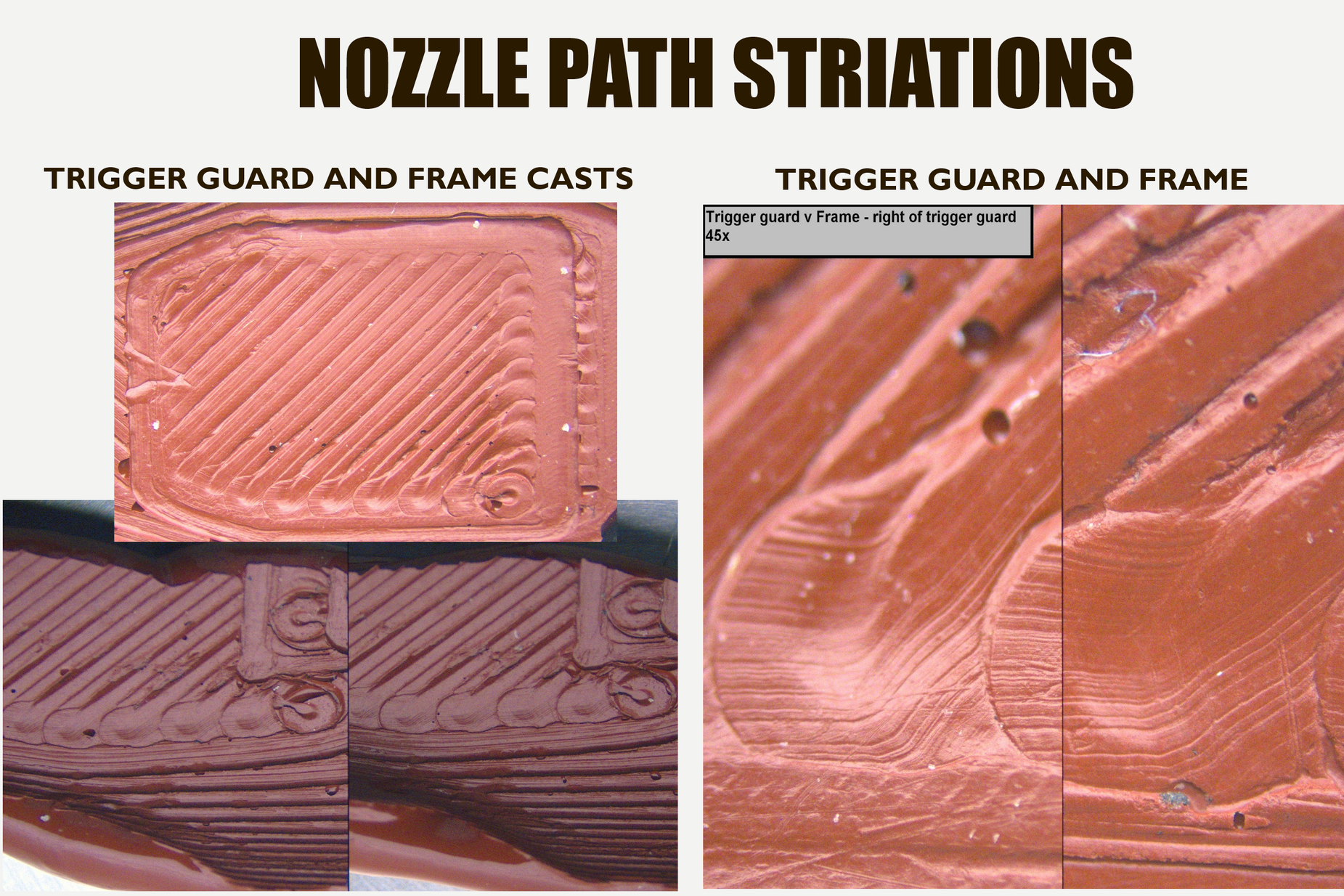

The material adds that fingerprints are run against DHS’s central repository of biometrics. To capture these, the user manual tells ICE officers to “align the subject’s fingers inside of the blue box and hold until the camera has captured the prints.”

ICE officers can use the tool to perform what the material describes as a “Super Query.” This includes querying multiple datasets at once related to “individuals, vehicles, airplanes, vessels, addresses, phone numbers and firearms,” according to the memo.

According to screenshots of the app viewed by 404 Media, the Super Query feature can search the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), which is an FBI-maintained database containing “missing persons and criminal information;” the Nlets system which includes whether someone has an outstanding state warrant against them; CBP’s system that screens people at the border called TECS; and another CBP database called the Seized Assets and Case Tracking System (SEACATS) that tracks material previously seized by CBP and ICE.

After scanning a face, fingerprints, or entering details about an identity document, the app can return a “SCREENED HITS FOUND” message, according to the user manuals. Those results include the subject’s name, nationality, age and date of birth, and unique identifiers such as their “alien registration,” and “CIV ID,” which is a system issued by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The results also include “Immig. Judge Decision,” presumably referring to whether an immigration judge has ruled on this person’s case, and “final order.” In the example given in the user manual, the immigration judge decision section says “remove.”

404 Media first revealed the existence of Mobile Fortify in June, based on leaked ICE emails, which showed ICE was repurposing data collected when people enter or exit the United States for enforcement inside the country.

Mobile Fortify differs from more well-known facial recognition tools, such as Clearview AI, because Clearview doesn’t necessarily have access to government databases. When a law enforcement officer uses Clearview, it checks a subject’s face against a massive archive of images Clearview has scraped from social media and the wider web. That can return someone’s name, potentially, and their social media presence. Mobile Fortify, meanwhile, takes someone’s identity and then burrows into DHS’s and other agencies' databases to surface much more information about the person, and information that only the government may possess.

404 MediaJason Koebler

404 MediaJason Koebler

The material indicates that Mobile Fortify may soon include data from commercial providers too. One section says that “currently, LexisNexis is not supported in the application.” LexisNexis is a massive data broker that collates data including peoples’ addresses, phone numbers, and associates. LexisNexis did not respond to a request for comment.

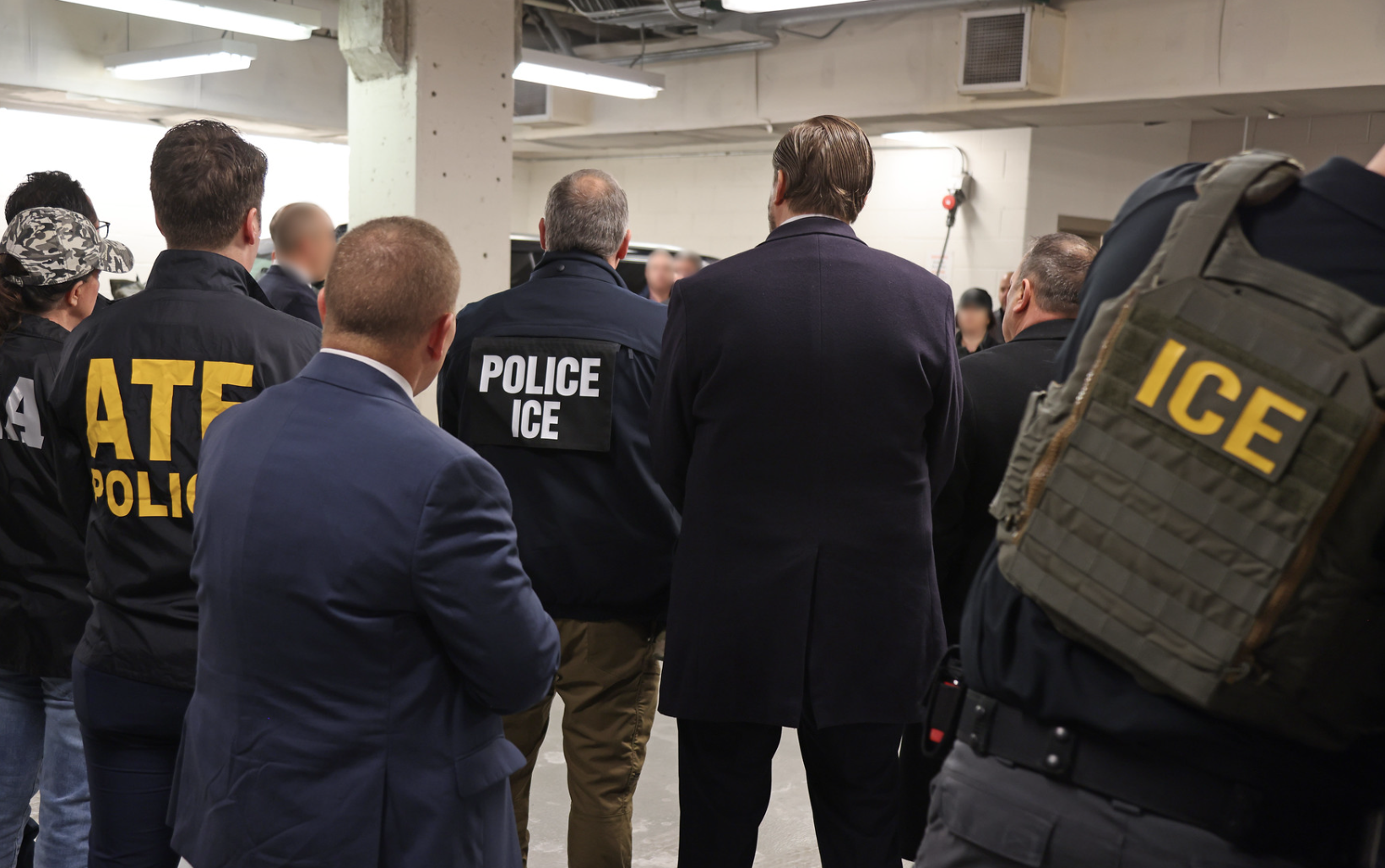

In videos posted to social media, ICE officers have repeatedly been seen pointing their phones in a way that suggested they were scanning or taking a photo of someone’s face. It is unclear whether the officers were using this tool or not.

Facial recognition technology can be inaccurate and lead to wrongful arrests. In one case, a Detroit man spent 30 hours in a jail cell because the technology thought he was a criminal, the New York Times previously reported.

“I worry ICE could be embracing a less accurate system because they’re indifferent to mistakes or even trying to build in systems that maximize chances of producing a ‘match’ that gives them a pro forma basis for stopping or detaining people, an especially accrue risk as ICE is being criticized in court for improper stops and racial profiling,” Jake Laperruque, deputy director of the Center of Democracy and Technology's Security and Surveillance Project, told 404 Media.

ICE has repeatedly made mistakes during its ongoing mass deportation effort, including detaining American citizens or raiding the wrong house.

ICE was recently granted a new budget of $28 billion.

DHS did not respond to a request for comment. The FBI deferred a request for comment to ICE. The State Department did not respond.