How the Trump tariffs differ from his first term

The president announces an audacious new tariff on social media. The media breathlessly quotes economists warning of peril ahead. The economy chugs along anyway.

Why it matters: While that was the pattern in 2018 and 2019, it may offer false comfort for what is to come in 2025.

- The Trump 2.0 trade war is already on a much larger scale, affecting many more products, than was ever seen in Trump 1.0.

The big picture: This time around, the president is choosing across-the-board tariffs over targeted ones, invoking a legal authority with fewer constraints, and not giving time for companies to plead their case for special exceptions.

- All of that increases the odds that the trade war will be more visible to Americans, disrupting supply chains and causing noticeable price hikes for certain items.

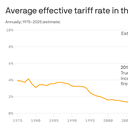

By the numbers: When Trump took office in 2017, tariff revenue was about 1.5% of total U.S. goods imports. By 2019, he had roughly doubled that to 2.9%, according to an analysis of federal data by the Yale Budget Lab.

- If the across-the-board tariffs implemented on Canada, Mexico and China this week remain in place the remainder of the year, that number is on track to soar to 9.5%, the highest since 1943.

- There were signs late yesterday the administration may be seeking to deescalate, but Trump has also threatened other large-scale tariffs, including on agriculture and automobiles.

Flashback: The 2018 to 2019 tariffs were implemented by invoking Sections 232 and 301 of trade statutes, the former giving the president authority to impose duties on national security grounds and the latter to combat unfair trade practices.

- Those laws demand a process of studies and appeals, which slowed their implementation while preventing unintended consequences.

By contrast, this week's new round of tariffs invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which gives the president broad powers with few checks "to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat."

What they're saying: "During Trump's first term there was breathless coverage and obsession over tariffs but without any obviously discernible economic impact," Harvard's Jason Furman tells Axios. "This time around it is the opposite. The tariffs are just one of many, many stories."

- "But lost in that massive onslaught is the fact that they are much bigger, are coming much faster, and this time you may actually start to see them in the macro data," he says.

Reality check: That does not necessarily mean an abrupt slowdown, or a recession, or 2022-style inflation. The United States is a large country that grows most of its own food and generates most of its own energy.

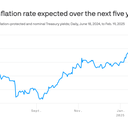

Yes, but: Mainstream estimates point to this round of tariffs having economic impacts large enough for Americans to feel.

- Nationwide chief economist Kathy Bostjancic estimates that if sustained, they would subtract 1 percentage point from GDP growth this year and raise inflation by 0.6 percentage points.

- "The deterioration in confidence could very well lead businesses to pare or at least delay investments and new hires, consumers to delay purchases, and for financial risk assets, such as equities, to decline or increase in volatility," she writes in a note.