Scientists Discover Ancient Farms in the Deep Sea

Welcome back to the Abstract!

It’s hard to keep up with all the news about all the giant gassy orbiters out there. I’m speaking, of course, about hot Jupiters, a class of planets that takes the concept of “inhospitable” to dazzling and creative new levels, and which had an epic news week.

Then, what did scientists find in cores taken from deep-sea trenches? The answer might surprise you. Next, mice administer “first aid.” Last, fish can see you for who you really are (though yummy treats will certainly not be refused).

Hot Jupiters Are So Hot Right Now (and at All Other Times)

Seidel, Julia et al. “Vertical structure of an exoplanet’s atmospheric jet stream.” Nature.

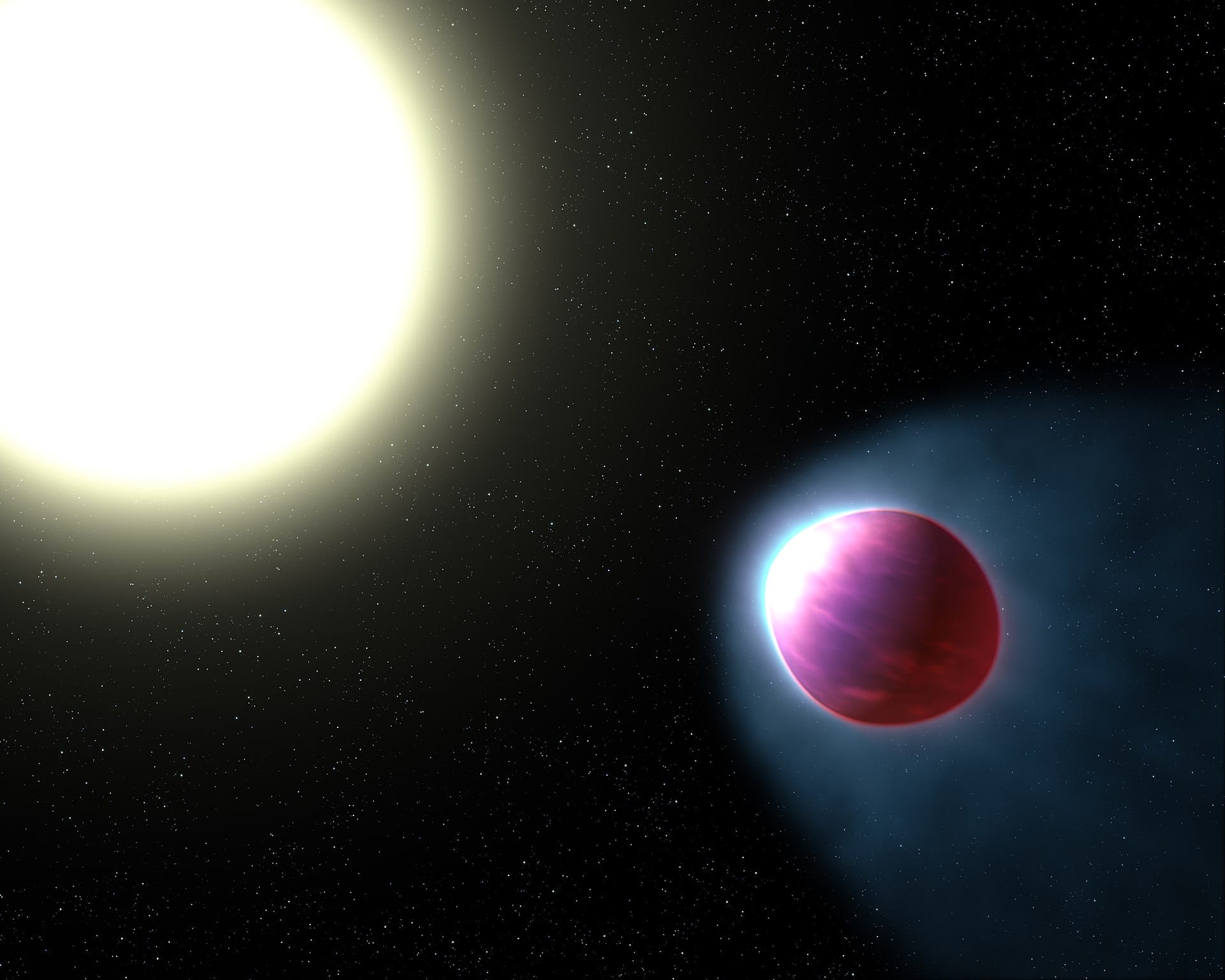

Hot Jupiters are the low-hanging fruit of exoplanet discoveries. As the name implies, they are Jupiter-sized worlds that orbit extremely close to their stars, a proximity that makes them—you guessed it—hot.

Given that they are both giant in scale and have short years lasting only hours or days, hot Jupiters are the easiest exoplanets to spot, which is why our catalog of distant worlds is packed with them. In fact, a study came out just this week that identified seven new ones.

But while it’s not all that novel to discover these worlds (which is kind of amazing in itself), scientists have now peered deep into the atmosphere of the hot Jupiter WASP-121, nicknamed Tylos, which is about 850 light years from Earth. It’s the first time several distinct atmospheric layers and processes have been observed on an exoplanet.

“Ultra-hot Jupiters, an extreme class of planets not found in our solar system, provide a unique window into atmospheric processes,” said researchers led by Julia Seidel of the European Southern Observatory (ESO). “Here we show a dramatic shift in atmospheric circulation in an ultra-hot Jupiter” including “the first vertical characterization of a high-altitude, super-rotational atmospheric jet stream.”

Tylos is slightly bigger than Jupiter, but it is so close to its star that its year lasts only 30 hours. As a consequence, it is tidally locked, meaning that one side is always facing the star, and the other always faces away. The star-lit side is about 2,300°C (4,200°F) which is, as advertised, quite hot. Using the ESO’s Very Large Telescope, the researchers spotted the aforementioned equatorial jet stream and saw flows of hot gas moving from the hot day side to the cooler night side—which is still pretty hot at around 700°C (1,340°F).

The weather report on Tylos is permanently fatal with a chance of titanium rain, according to a third study that came out this week (that’s a hot Jupiter hat-trick). Taken together, the research represents a new emerging era of exoplanet observations in which astronomers can peek under the hood of these distant atmospheres and start to get a real vertical cross-section of otherworldly skies.

Down the line, this will lead to better characterizations of the atmospheres of potentially habitable exoplanets, which could contain detectable signs of alien life. But for now, on this late winter weekend, let's be satisfied with warming ourselves into certain oblivion in the bellies of hot Jupiters.

From the Hadal to the Grave

Hovikoski, Jussi et al. “Bioturbation in the hadal zone.” Nature Communications.

To cool off, we shall now dive straight into the deepest parts of the ocean, the hadal zone, where strange things are inherently afoot. Scientists took sediment cores from seafloors at depths of over 4.6 miles in the Japan Trench which is, in my opinion, asking for trouble. But in this case, the results revealed an activity that you might not expect to find in one of the most inhospitable places on Earth—farming.

I should just say, the “farmers” are probably invertebrates, like sea cucumbers or bivalves, that cultivate microbes that help break down organic matter for them. Still, a basic form of “agrichnial” farming is preserved in trace fossils, like burrows, the team found in the cores.

“The hadal zone, >6 km deep, remains one of the least understood ecosystems on Earth,” said researchers led by Jussi Hovikoski of the Geological Survey of Finland. The cores open a rare window into this otherworldly region and reveal “slender spiral, lobate and deeply penetrating straight and ramifying burrow systems…interpreted to include burrows of microbe farming and chemosymbiotic invertebrates.”

The study also gets points for its title, “Bioturbation in the hadal zone,” which sounds like an early aughts prog rock album. \m/

Somebody Call an EMT! (Emergency Mouse Technician)

Humans produce a lot of selfish psychos, if you hadn’t noticed, but one nice thing about our species is we generally share a prosocial instinct to help people during a medical crisis. As it turns out, we’re not alone in this behavior, according to a new study that monitored the reactions of mice to ailing, unconscious, or dead conspecifics.

“Anecdotal observations across several species in the wild, including nonhuman primates, dolphins, and elephants have reported intriguing behaviors of animals toward unresponsive conspecifics that have collapsed because of sickness, injury, or death,” said researchers led by Wenjian Sun of the University of Southern California. “These animals…display various behavioral responses, including touching, grooming, nudging, and sometimes even more intense physical actions, such as striking, toward the collapsed peers. Some of these actions toward incapacitated conspecifics are reminiscent of human emergency responses, especially those involving sensory stimulation.”

To bring these anecdotal reports in an experimental setting, the team videotaped mice responding to cagemates that had been anesthetized into unconsciousness, as well as their reactions to dead mice. The r mice interacted with unconscious cage-mates about ten times as much as with an active partner, and may have even performed basic versions of first aid.

“Our results suggest that the actions of mouth/ tongue biting and tongue pulling may have rescue-like effects, reminiscent of human first aid efforts in reviving unconscious individuals with physical stimulation and airway maintenance,” the researchers said.

“The consequences of the behaviors, such as improved airway opening or clearance and expedited recovery, are clearly beneficial to the recipient,” they added, though they also cautioned that “it is challenging to determine the motivational needs behind these distinctive ‘reviving-like’ behaviors.”

Familiarity played a strong role in the experiment's outcome; mice heaped much more attention on dead or unconscious cage-mates that they knew well compared to strangers. At the risk of anthropomorphizing, it’s kind of sad to think about these mice being confronted with their passed-out or dead friends, but the silver lining is an empirical validation of widespread prosocial behaviors.

I’m also going to assume it means that the Disney franchise The Rescuers, starring mice humanitarians, is a documentary.

The Adventures of Left Hump and Friends

The next time you go for an ocean swim, why not introduce yourself to some neighboring fish? They might learn to recognize you as an individual and start following you around, especially if you give them something nice to eat. That’s the conclusion of a new study that found fish can tell individual divers apart based on visual cues—and that they rapidly learn which divers are generous with treats (in this case: shrimp).

Researchers Maëlan Tomasek and Katinka Soller conducted several dives at the STARESO research station in Corsica, France. Soller was the designated shrimp dispenser, and the wild fish “volunteers” rapidly learned to distinguish her visually from Tomasek, the shrimp miser.

“Two species voluntarily took part in our experiments: saddled sea bream O. melanura and black sea bream S. cantharus,” said the researchers. “Of specific individuals, the saddled bream (Bernie) was first identified at dive 5 of the training, four black bream at dives 12 (Left Hump), 15 (Kasi), 19 (Alfi), 21 (Julius) and the last black bream (Geraldine) on the first session of experiment 1. Note that this marks the moment from which we were able to reliably identify them (i.e. identify with absolute certainty at each apparition from one dive to the next) but that they most likely appeared several days prior to this.”

First of all, fantastic names. I’m already shipping Julius and Geraldine as a celebrity fish couple called Juladine. Left Hump will officiate the wedding. But setting aside the fish fanfic, the team demonstrated that the fish learned to visually tell the researchers apart, leading to a clear preference for following Soller.

“The fact that wild bream can discriminate between divers adds scientific evidence to the numerous accounts suggesting differentiated relationships between fish and specific humans,” the team said. “Our study thus encourages a reappraisal of the methodological avenues to study cognitive abilities of wild fish under natural conditions.”

“It also demonstrates a potential difficulty when conducting such experiments that could be disturbed by fish following specific experimenters,” the researchers said, concluding with an implied wink: “Researchers might not always want to be followed all around by fish, but if they do, they will not be disappointed.”

Thanks for reading! See you next week.