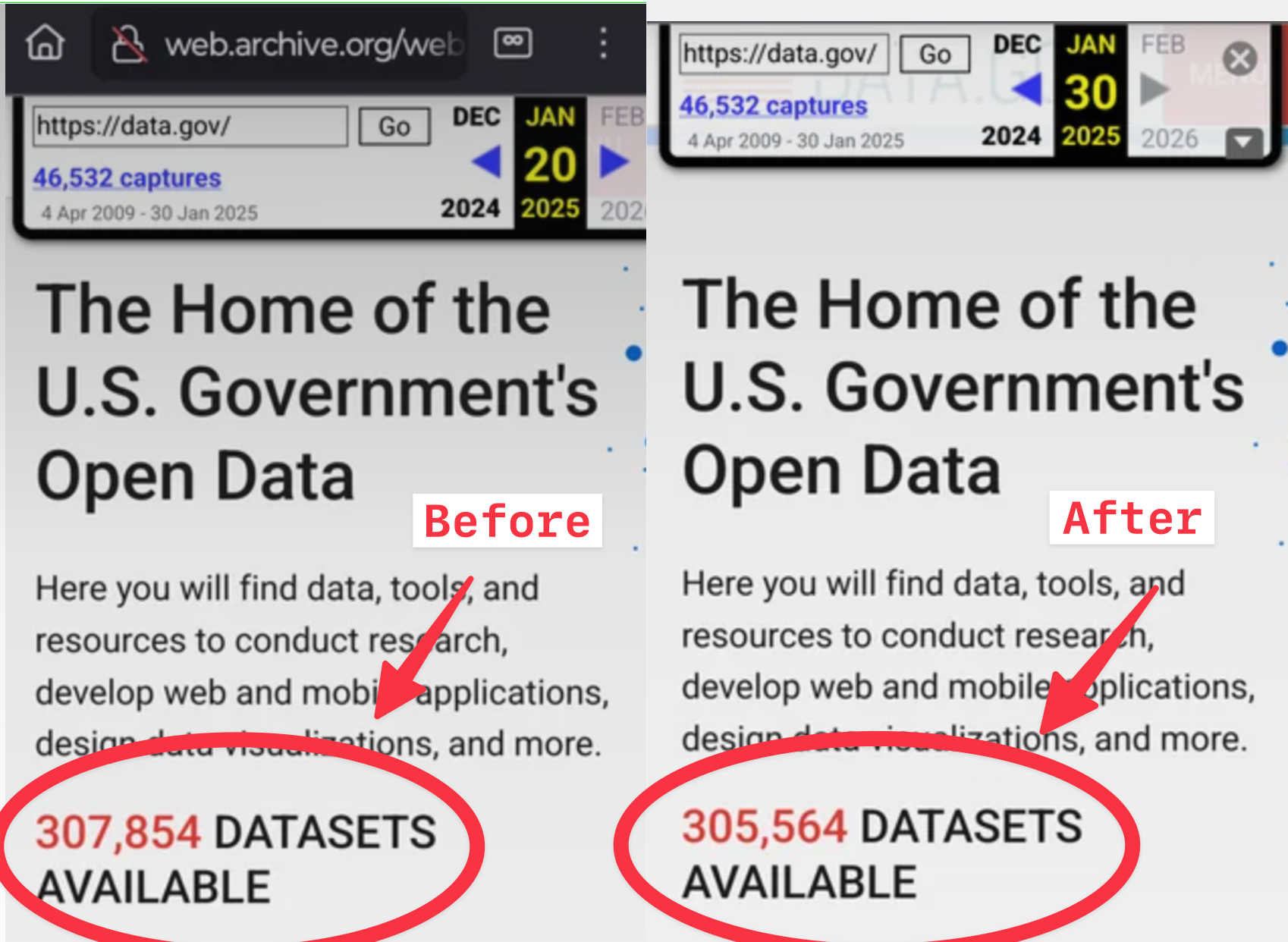

Datasets aggregated on data.gov, the largest repository of U.S. government open data on the internet, are being deleted, according to the website’s own information. Since Donald Trump was inaugurated as president, more than 2,000 datasets have disappeared from the database.

As people in the Data Hoarding and archiving communities have pointed out, on January 21, there were 307,854 datasets on data.gov. As of Thursday, there are 305,564 datasets. Many of the deletions happened immediately after Trump was inaugurated, according to snapshots of the website saved on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. Harvard University researcher Jack Cushman has been taking snapshots of Data.gov’s datasets both before and after the inauguration, and has worked to create a full archive of the data.

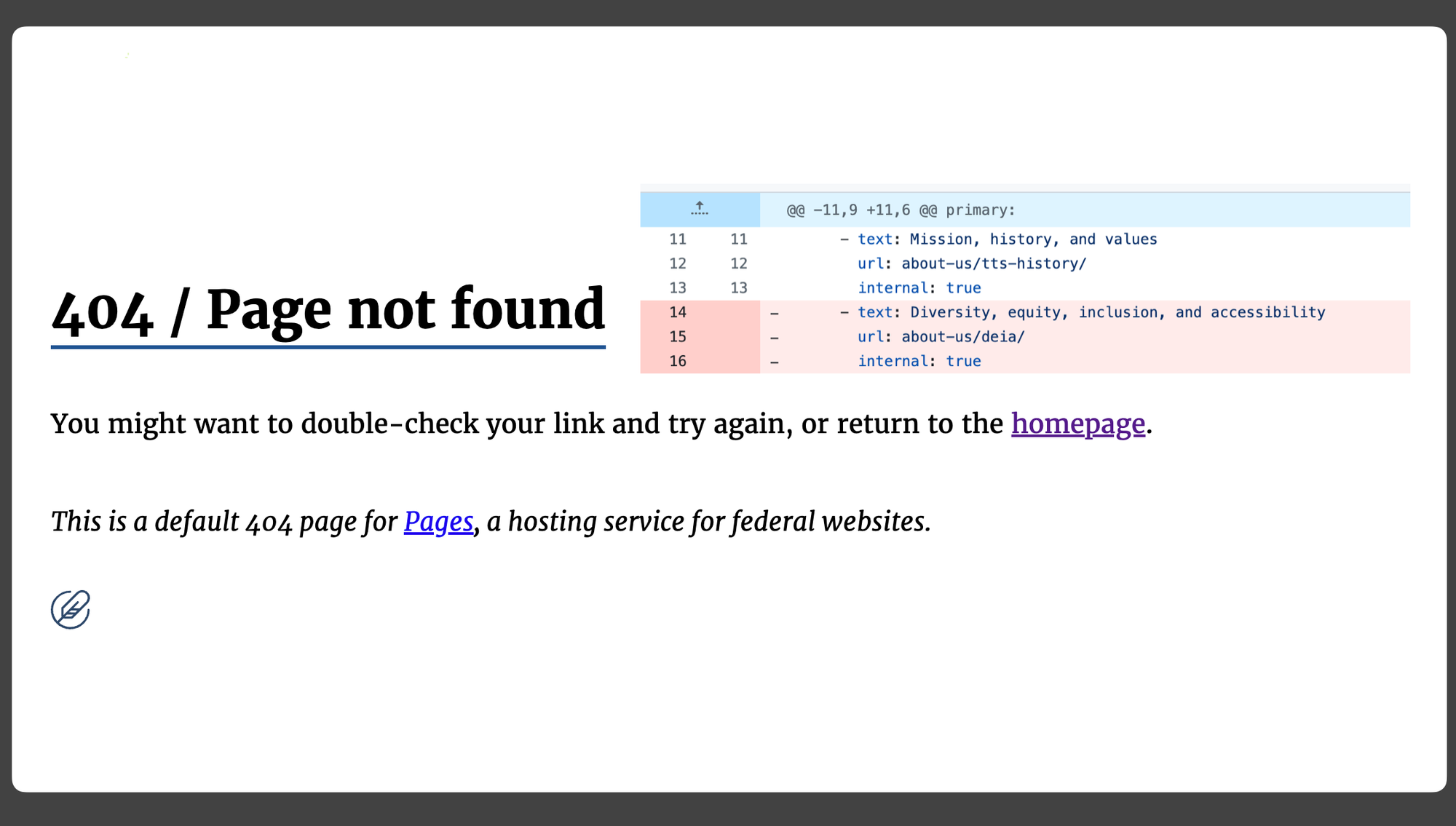

Because data.gov is an aggregator that doesn’t always host the data itself, this doesn’t always mean that the data itself has been deleted, that it doesn’t exist elsewhere on federal government websites, or that it won’t be re-hosted elsewhere. Further research will be necessary to determine what has happened to any given dataset, or to see if it turns up elsewhere on a government website. For example, 404 Media found some datasets in Cushman’s analysis that are no longer accessible on data.gov but can still be found on individual agency websites; we also found some datasets that seem to still exist because data.gov links to working websites but give a file-not-found error message when trying to download the file itself.

Disproportionately, the datasets that are no longer accessible through the portal come from the Department of Energy, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of the Interior, NASA, and the Environmental Protection Agency. But determining what is actually gone and what has simply moved or is backed up elsewhere by the government is a manual task, and it's too early to say for sure what is gone and what may have been renamed or updated with a newer version.

This is because data.gov doesn’t always host the data that it is indexing. Sometimes the data is hosted directly on data.gov, but other times it links to an individual agency’s website, where the data is actually hosted. This means archiving and analyzing data.gov is not straightforward.

“Some of [the entries link to] actual data,” Cushman told 404 Media. “And some of them link to a landing page [where the data is hosted]. And the question is—when things are disappearing, is it the data it points to that is gone? Or is it just the index to it that’s gone?”

For example, “National Coral Reef Monitoring Program: Water Temperature Data from Subsurface Temperature Recorders (STRs) deployed at coral reef sites in the Hawaiian Archipelago from 2005 to 2019,” a NOAA dataset, can no longer be found on data.gov but can be found on one of NOAA’s websites by Googling the title.

“Stetson Flower Garden Banks Benthic_Covage Monitoring 1993-2018 - OBIS Event,” another NOAA dataset, can no longer be found on data.gov and also appears to have been deleted from the internet. “Three Dimensional Thermal Model of Newberry Volcano, Oregon,” a Department of Energy resource, is no longer available via the Department of Energy but can be found backed up on third-party websites.

Determining what is gone, why it’s gone, and where it went seems like it would be straightforward, and it would seem like you could attribute all of it to malice on the part of an administration that has declared war on climate change and government equity efforts. But archivists who have been working on analyzing the deletions and archiving the data it held say that while some of the deletions are surely malicious information scrubbing, some are likely routine artifacts of an administration change, and they are working to determine which is which. For example, in the days after Joe Biden was inaugurated, data.gov showed about 1,000 datasets being deleted as compared to a day before his inauguration, according to the Wayback Machine.

Because of the overall large number of datasets as well as the way that data.gov works, it is still too early to say what, specifically, has been deleted, though archivists and academics like Cushman are working on triaging the situation. It can reasonably be surmised that climate and environmental research and data, as well as research about marginalized communities and minorities are among the datasets that have been purged. This is in part because the Trump administration deleted huge swaths of climate data during his first term, and because Trump issued an executive order asking all federal agencies to delete anything related to diversity, equity and inclusion.

Data.gov serves as an aggregator of datasets and research across the entire government, meaning it isn’t a single database. This makes it slightly harder to archive than any individual database, according to Mark Phillips, a University of Northern Texas researcher who works on the End of Term Web Archive, a project that archives as much as possible from government websites before a new administration takes over.

“Some of this falls into the ‘We don’t know what we don’t know,’” Phillips told 404 Media. “It is very challenging to know exactly what, where, how often it changes, and what is new, gone, or going to move. Saving content from an aggregator like data.gov is a bit more challenging for the End of Term work because often the data is only identified and registered as a metadata record with data.gov but the actual data could live on another website, a state .gov, a university website, cloud provider like Amazon or Microsoft or any other location. This makes the crawling even more difficult.”

Phillips said that, for this round of archiving (which the team does every administration change), the project has been crawling government websites since January 2024, and that they have been doing “large-scale crawls with help from our partners at the Internet Archive, Common Crawl, and the University of North Texas. We’ve worked to collect 100s of terabytes of web content, which includes datasets from domains like data.gov.”

The Environmental Data & Governance Institute (EDGI) published a report in 2019 detailing “How the Trump administration has undermined federal web infrastructures for climate information,” which included not just deleting datasets but also, in some cases, not deleting datasets but deleting the links to them, changing descriptions of them, or making them much harder to find. For example, during Trump’s first term, the Department of Transportation’s information on climate change was deleted, republished in a different form elsewhere, then deleted again from that new place, the report found.

James Jacobs, a Stanford Libraries researcher who also works with a group called Free Government Information,” told 404 Media in an email that data.gov “has always been kind of a government data junk drawer (I call it that lovingly ;-)). That is, it was a really great effort to get the vast federal apparatus to start to think about collecting and preserving data. But there are no specific regulations that tell agencies that they *have to* use data.gov. Some agencies use it heavily, some put up a few excel spreadsheets and called it a day.”

“I assume some of those datasets in data.gov have bad urls to old agency pages that no longer exist (it’s really problematic when an agency decides to redesign its site and its base domain changes and all the links to important information and data are broken),” Jacobs added. “Some of it is probably link rot and content drift and some of it is no doubt Trump admin policy driven (e.g. anything having to do with DEI).”

Harvard’s Cushman said that, because this is the internet, there are always things that are being added, breaking, changing, or vanishing, and that some of this happens on purpose and some of it happens on accident. So determining what is being purged, when there are so many data points, is not always trivial. “If you want to answer why any given thing is gone, it becomes an individual research question.” Cushman said he is working on compiling this info now and will publish it soon.

All of this is to say that even under the best circumstances, government datasets and research can get lost or deleted, and archiving it is not always easy. When an administration specifically makes a point of deleting research, this already fragile ecosystem is stressed even further. All of these suddenly disappeared datasets must be taken in with the context that we know the Trump administration has ordered agencies to delete and edit specific webpages, and 404 Media’s own reporting has shown targeted deletions of pages relating to diversity, equity, and inclusion as well as climate change.

In a post from this week on Free Government Information, Jacobs explained that “the government information crisis is bigger than you think.”

“There is a difference between the government changing a policy and the government erasing information, but the line between those two has blurred in the digital age,” Jacobs wrote. He explained that before the internet, government documents were printed and were archived by being distributed among many different libraries as part of the “Federal Depository Library Program.” The internet has made a lot of government information more accessible, but it has also made it a lot more fragile.

“In the print era, libraries did a good (but not perfect) job of preservation through inertia (ie collect and catalog a document, put it on a shelf, and leave it there until a patron wanted it),” Jacobs told 404 Media in an email. “In the digital era, that system of distribution/preservation/access has broken down because digital publications are no longer ‘distributed’ to libraries, and government entities a) publish a LOT more on the internet; but b) have no clear regulations or policies regarding preservation.”

It is absolutely true that the Trump administration is deleting government data and research and is making it harder to access. But determining what is gone, where it went, whether it’s been preserved somewhere, and why it was taken down is a process that is time intensive and going to take a while.

“One thing that is clear to me about datasets coming down from data.gov is that when we rely on one place for collecting, hosting, and making available these datasets, we will always have an issue with data disappearing,” Phillips said. “Historically the federal government would distribute information to libraries across the country to provide greater access and also a safeguard against loss. That isn't done in the same way for this government data.”